Every day, on average, seven kids and teens are shot dead in America. Election 2016 will undoubtedly prove consequential in many ways, but lowering that death count won’t be one of them. To grapple with fatalities on that scale—2,500 dead children annually—a candidate would need a thoroughgoing plan for dealing with America’s gun culture that goes well beyond background checks. In addition, he or she would need to engage with the inequality, segregation, poverty, and lack of mental health resources that add up to the environment in which this level of violence becomes possible. Think of it as the huge pile of dry tinder for which the easy availability of firearms is the combustible spark. In America in 2016, to advocate for anything like the kind of policies that might engage with such issues would instantly render a candidacy implausible, if not inconceivable—not least with the wealthy folks who now fund elections.

So the kids keep dying and, in the absence of any serious political or legislative attempt to tackle the causes of their deaths, the media and the political class move on to excuses. From claims of bad parenting to lack of personal responsibility, they regularly shift the blame from the societal to the individual level. Only one organized group at present takes the blame for such deaths. The problem, it is suggested, isn’t American culture, but gang culture.

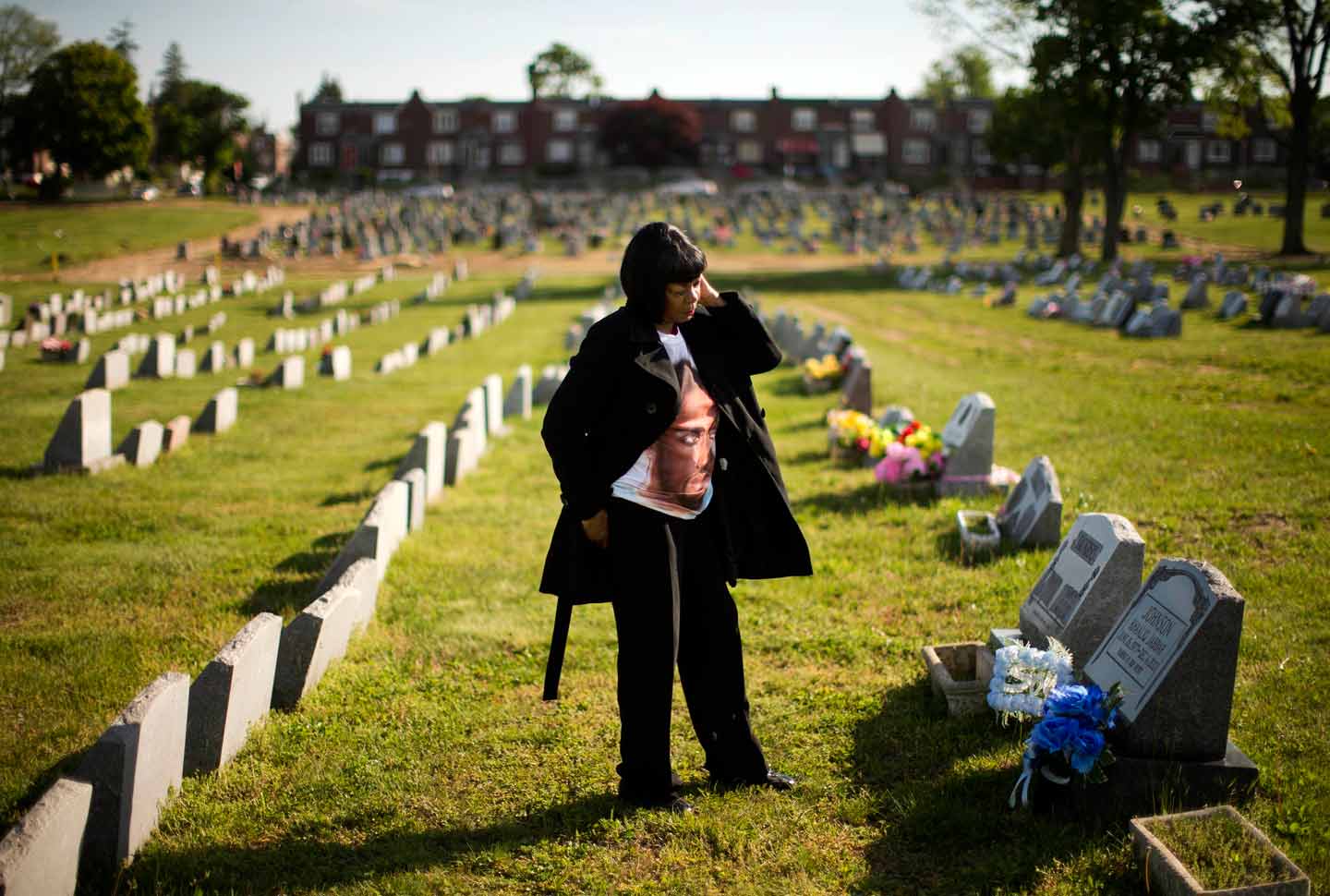

Researching my new book,

, about all the children and teens shot dead on a single random Saturday in 2013, it became clear how often the presence of gangs in neighborhoods where so many of these kids die is used as a way to dismiss serious thinking about why this is happening. If a shooting can be described as “gang related,” then it can also be discounted as part of the “pathology” of urban life, particularly for people of color. In reality, the main cause, pathologically speaking, is a legislative system that refuses to control the distribution of firearms, making America the only country in the world in which such a book would have been possible.

The obsession with whether a shooting is “gang related” and the ignorance the term exposes brings to mind an interview I did 10 years ago with septuagenarian Buford Posey in rural Mississippi. He had lived in Philadelphia, Mississippi, around the time that three civil-rights activists—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—were murdered. As I spoke to him about that era and the people living in that town (some of whom, like him, were still alive), I would bring up a name and he would instantly interject, “Well, he was in the Klan,” or “Well, his Daddy was in the Klan,” or sometimes he would just say “Klan” and leave it at that.

After a while I had to stop him and ask for confirmation. “Hang on,” I said, “I can’t just let you say that about these people without some proof or corroboration. How do you know they were in the Klan?”

“Hell,” he responded matter-of-factly, “I was in the Klan. Near everybody around here was in the Klan around that time. Being in the Klan was no big deal.”

Our allegiances and affiliations are, of course, our choice. Neither Posey nor any of the other white men in Philadelphia had to join the Klan, and clearly some were more enthusiastic participants than others. (Posey himself would go on to support the civil rights movement.)