As Oswald Dixon was laid to rest in Salford on Wednesday the heavens wept. One hundred years old and with no traceable family, when he died on 25 September the staff at his care home feared no one would come to his funeral. They put out an appeal for mourners. And on a rainswept midweek afternoon about 300 showed up.

Dixon was, by all accounts, a charming man with a wonderful sense of humour who had lost his sight and succumbed to dementia in his later years. At his 100th birthday party he said that he always tried to live life as it should be lived, by doing things for other people.

But the overwhelming majority of those who attended did not know him. They were drawn not by his personality but by his story. Here was a man born in Kingston, Jamaica, in April 1919, just a few months before racial pogroms swept through many British cities, including Salford. He joined the Royal Air Force in Jamaica as a flight mechanic. He moved to Britain before the end of the second world war and remained in the service to teach new recruits until he retired.

Not much else is known about him. A man came with his family all the way from Dublin claiming to be Dixon’s estranged son – a link nobody could verify in the moment. But what was known was enough. People came from Birmingham, Cheltenham and London to see him off. The lord mayor of Liverpool sent a wreath. RAF cadets and members of 34 Squadron carried the coffin into the chapel. The Last Post was played; Amazing Grace and Eternal Father in the Sky were sung. It was not so much the passing of man but a moment. A chance to commemorate an unknown soldier, one of the last from a community whose contributions had been airbrushed from the collective memory. A chance to publicly reclaim not only a person, but a history we were never taught and have had to claim for ourselves.

“I didn’t know him,” Tony Bryan who came, from Cheltenham, told the BBC. “It’s not about the expense, it’s not about the distance, I just had to be here.”

“As a first-generation British person with Caribbean heritage, this was important to us,” Sheron Burton-Francis, from Old Trafford, told Manchester Evening News. “It was very moving and only confirmed that Oswald did have a family within the Caribbean community.”

“About 50 years from now,” wrote Ruth Glass in her 1960 book London’s Newcomers, “future historians writing about Europe will presumably devote a chapter to the coloured minority group in this country. They will say that although this group was small, it was an important, indeed an essential one. For its arrival and growth gave British society an opportunity of recognising its own blind spots, and also of looking beyond its own nose to a widening horizon of human integrity.”

The response to the appeal for Dixon’s funeral illustrates the degree to which Britain is, and has been, capable of rising to that challenge. Alongside our brutal history of racism stands an impressive record of anti-racism, in which people of all ethnicities have fought for greater inclusivity and equality against all odds. Indeed, the fact that we enjoy any multiracial conviviality – and we do – is not the product of our inherent genius or innate sense of fair play as a nation. Our capacity to get along – to live, love, work and support – did not wash up with the time and tide: it was won, in battles local and national, collective and individual, systemic and interpersonal, by those who recognised the blind spots and sought to widen the horizon.

The potential, in this regard, is evident if not always obvious. We are far more compassionate, decent and open-minded than our politics, and particularly our rhetoric, suggests. The reality, however, indicates that such flashes of human empathy and solidarity often sit alongside a far more enduring bureaucratic and institutional callousness.

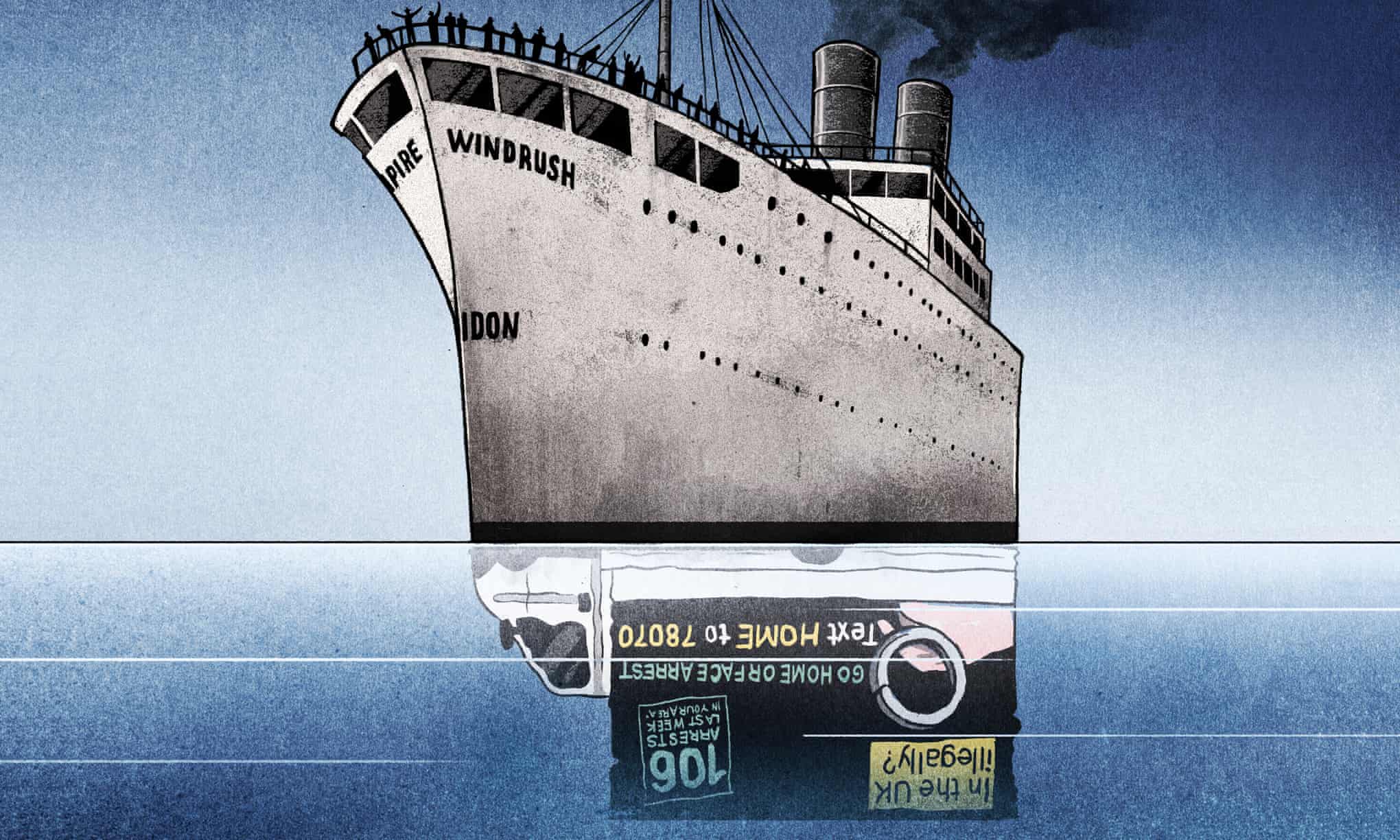

Oswald Dixon arrived in Britain four years before HMS Windrush docked. The children of many who came not long after him lived for years with the threat of deportation, having been traumatised, pauperised and, at times, even exiled by draconian immigration legislation that was renounced and disavowed but never actually repealed. Indeed the truly scandalous element of the Windrush scandal, at this point, is not the laws that made people lose their homes, livelihoods, health and freedom, sending British citizens to jail and abroad for the crime of being born to the wrong parents at the wrong time. The scandal is that we know all this, nothing has changed as a result, nobody has paid any serious price apart from the victims and the nation appears to be carrying on, politically at least, as if that’s OK. It’s not.

As of July, those whose lives were shattered when they were unlawfully stripped of their citizenship had not received compensation payments, and the overwhelming majority still have not received anything. Some have died waiting. Others remain in desperate need, since the scandal lost them their jobs. Leaked extracts of the “Windrush lessons learned” review, commissioned by Sajid Javid when he was at the Home Office, accuse officials of recklessness, denial and a reluctance to learn from their mistakes. The report’s author, Wendy Williams, writes: “While everyone I spoke to was rightly appalled by what happened, this was often juxtaposed with a self-justification, either in the form of it was unforeseen, unforeseeable and therefore unavoidable … or a failure on the part of individuals to prove their status.”

And surveys within the Home Office agencies at the heart of the scandal suggest a culture of pervasive racism and discrimination internally, with more than a fifth of staff at Border Force, the part of the Home Office responsible for border control, experiencing discrimination while carrying out their duties – the worst figure for any of the UK’s 89 government agencies and departments.

Meanwhile, Glyn Williams, a director general at the Home Office and an architect of the hostile environment policy that made the scandal possible, was named in the Queen’s birthday honours as a knight commander of the Order of the Bath. Amber Rudd, the home secretary forced to resign over Windrush, spent six months on the backbenches before returning as work and pensions secretary.

Oswald Dixon is part of the same story as those who have endured the Windrush scandal. It is a story of empire, migration and service. To commemorate one and neglect the other is to say that we value people more in their death than in their life; that we recognise their sacrifice but not their suffering; that we know what decency looks like, we just won’t fight for it.

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist