“You can tell a true war story by the way it never seems to end,” wrote Tim O’Brien in his novel about Vietnam, The Things They Carried. “Not then, not ever. In a true war story, if there’s a moral at all, it’s like the thread that makes the cloth. You can’t tease it out. You can’t extract the meaning without unravelling the deeper meaning.”

For all the ways in which US politics remain unpredictable, the presence of the Vietnam war as an episodic inflection point remains constant. Only last week, after Donald Trump declared a ban on some transgender people serving in the military, it was pointed out that he avoided serving in Vietnam thanks to five deferments, the last for “bone spurs in his heels”. (When asked which heel a few years ago he couldn’t remember.) More than 40 years after the fall of Saigon, it continues to influence how Americans view politics at home.

What has been true for Vietnam and America has become the case for Britain and Iraq. It is 15 years this month since Britain and the US invaded Iraq. The most important consequences of that war are, of course, in the place where it was fought, where it has left an estimated million people dead, destabilised a region, and spawned far more jihadist terror, including Isis, than it could ever have thwarted.

The invasion’s legality and validity have been debated constantly, not least on these pages. But the legacy it bequeathed our political culture is less often acknowledged, even as it remains deep and enduring.

Its most obvious impact has been its contribution to Labour’s current trajectory. Jeremy Corbyn’s stance on the war is a significant element of his appeal. When the largest march in British history took place against the war, he spoke from the podium. When he stood for leader he said it was illegal, that if elected he would apologise for it, and that if it were ever deemed a war crime, Tony Blair should go on trial. All his opponents who were MPs at the time voted for it; the one who wasn’t, Liz Kendall, voted against investigating it.

It is also one of the reasons Corbyn’s parliamentary colleagues struggled to find a viable candidate to oppose him when they launched their coup. They were sufficiently aware of the popular mood to realise that they needed someone who wasn’t tainted by having voted for the war. That counted out most senior Labour parliamentarians with any ministerial experience. Owen Smith was championed, in part, because he hadn’t been an MP when the vote took place. But unlike Corbyn, his position on the war lacked clarity or consistency. During the leadership campaign he said he had been opposed to the war at the time; but in 2006 he said that at the time of the invasion he had thought it was part of a “noble, valuable, tradition”, and he didn’t know whether he would have voted against it.

As the situation deteriorated and no WMDs were found, the war contributed to a general sense of cynicism

Iraq is also the primary and overriding reason why Blair could win three elections and yet now barely get a hearing in his own party, let alone beyond. Maintaining that he made the right decision and that the world is safer for it, he has opted to protect his legacy over restoring his credibility, and ended up sacrificing both.

But the ramifications of Iraq go way beyond Labour, to a broader matter of trust between the public and the establishment. A year after the invasion, 60% said they had lost trust in ministers. Almost a decade after that, a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit argued Britain was “beset by a deep institutional crisis” with trust in government, parliament and politicians “at an all-time low”. The British Social Attitudes survey of 2013 concluded: “Those who govern Britain today have an uphill struggle to persuade the public that their hearts are in the right place.”

Public trust waxes and wanes with the moment, and Iraq is not, of course, the sole prism through which these trends can be understood. There has been the financial crisis, austerity, MPs’ expenses, the NHS and phone hacking, to name but a few. And people forget that for most of the war’s first year, it was relatively popular. But as the situation deteriorated and no weapons of mass destruction were found, it contributed to a general sense of cynicism.

Where politicians went in the public estimation, journalists followed. The willingness of so much of the media to uncritically accept the government’s case eroded confidence in journalism. When the government claimed Iraq could use weapons of mass destruction in 45 minutes, some acted less like journalists than stenographers: “45 minutes from attack” was the London Evening Standard front-page headline. “He’s got ’em let’s get him,” wrote the Sun. Liberal and left scepticism about the mainstream media over Iraq would later spread rightwards and find different targets and justifications – some more spurious than others. But if this was not the beginning of a popular wariness that we were being fed what is now termed “fake news”, then it was at least a step-change in that direction.

Meanwhile, playing fast and loose with facts, misleading the public, producing dossiers full of lies, and ignoring or distorting expertise – all of which were central to the war effort – helped contribute to a culture in which experts are not valued, and facts are considered optional. When the political class wonders how our discourse has become so diminished, self-destructive and coarsened that the country is capable of rejecting the warnings of economists, presidents and specialists, they could do worse than start with the war that most of them supported.

“I think Iraq is connected with Brexit,” Jeremy Greenstock, a former British ambassador to the UN, told Huffington Post a few months after the EU referendum. “The linkages can be traced from the protests over Iraq in 2003 to the vote in the June 2016 referendum to leave the EU: ‘The people up there in charge just do not seem to be taking our views into account.’”

There are some who believe that this obsession with a decision made 15 years ago about a war in which combat operations ended nine years ago is perverse. This is deeply misguided. First, because many are still living with the consequences. Amnesia is the privilege of the powerful. The powerless do not have the luxury of moving on, because their nations have been flattened, economies ruined and sectarian divisions deepened and weaponised as a result of a war that was prosecuted in their name.

Second, it was the greatest foreign policy error of a generation or more, in which most of the political class and the media class were entirely complicit. We cannot walk away – because it has changed who we are, and so wherever we go, this dark shadow follows us.

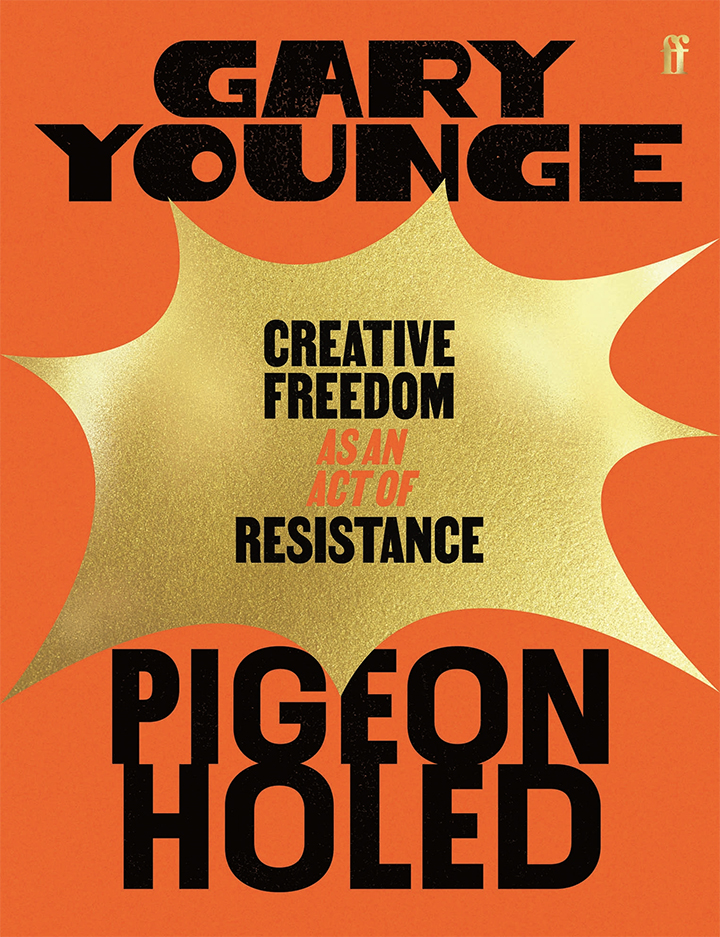

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist