About every three months I am accused of being an anti-semite. It is not difficult to predict when it will happen. A single, critical mention of Israel's treatment of Palestinians will do it, as will an article that does not portray Louis Farrakhan as Satan's representative on earth. Of the many and varied responses I get to my work - that it is anti-white (insane), anti-American (inane) and anti-Welsh (intriguing) - anti-semitism is one charge that I take more seriously than most.

This is not because I believe I consciously espouse anti-semitic views, but because I do not consider myself immune to them. There is no reason why I should not be prone to a centuries-old virus that is deeply rooted in western society. That does not mean that I accept the charges uncritically. I judge them on their merits and so far have found them wanting. But I do not summarily dismiss them either; to become desensitised to the accusation would be to become insensitive to the issue. It is a common view on the left that political will alone can insulate you from prejudice. It stems, among some, from a mixture of optimism and arrogance which aspires to elevate oneself above the society one is trying to transform.

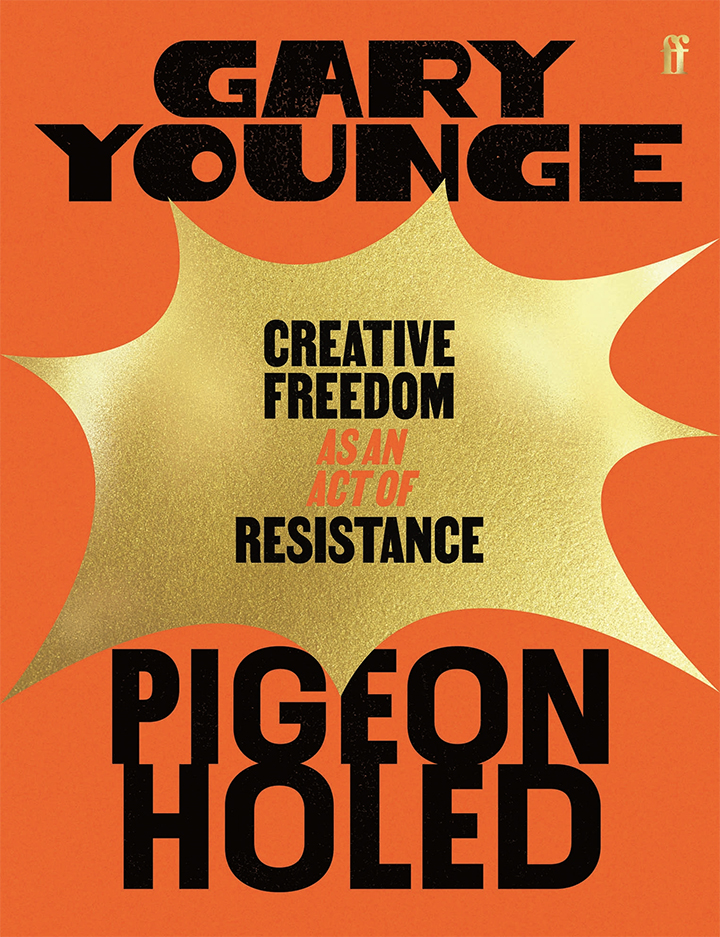

Last month's New Statesman front page of a shimmering golden Star of David impaling a union flag, with the words "A kosher conspiracy?" was a case in point. Some put it down to an editorial lapse of judgment. But many Jews saw it not as an aberration but part of a trend - one more broadside in an attack on Jews, not from the hard right but the liberal left. The New Statesman's editor apologised, but the response of some progressives has been defensive and confused, because they fail to that the more they accommodate, excuse or ignore anti-semitism, the less they are qualified to preach about Israel.

Anti-semitism existed long before Israel did and played the decisive role in winning over the vast majority of Jews to the Zionist cause. But Judaism is not Israel. And while it is difficult, in the current climate, to understand the Jewish community's concerns without reference to Israel, it is vital not to confuse the two. To do so opens the door for both anti-semites and apologists for Israeli aggression in the Middle East.

"Signs of leftist and Islamist anti-semitism are rife in Britain these days and Jews are worried," claimed an article in Israel's most leftwing mainstream newspaper, Ha'aretz, a few weeks ago. Sadly, the facts which might verify these claims were, for the most part, lacking. Research conducted by the Community Security Trust, an organisation which aims to provide advice and security for British Jews, showed a "sharp increase" in anti-semitic attacks over the past four years. But the groups which are by far the most vulnerable to racist attack remain Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, who are overwhelmingly Muslim.

Since there is no suggestion that the left is responsible for these anti-semitic attacks, the evidence of an anti-semitic revival among its numbers remains anecdotal. The British left has a strong record of fighting anti-semitism, but there can be little doubt that today anti-semitism does find a specific expression among the left. Believing that wealth disqualifies Jews from being among the oppressed, leftwingers fail to take anti-semitism as seriously as other forms of discrimination. Based on the stereotype of "the wealthy Jew", such a view is not just insulting but ignores the nature and history of anti-semitism and the considerable pockets of poverty within the Jewish community. Moreover, Jews on the left complain of feeling themselves under suspicion for their private attachment to Israel, and their presumed support for all that it does.

Such presumptions and prejudices are morally wrong. And because they are wrong in principle they remain a liability in politics. In the same way that the racism and historical amnesia of the right weaken its arguments against Robert Mugabe and Zimbabwe, every example of anti-semitism devalues whatever opinions are given about Israel's role in the Middle East. It does not invalidate the arguments - Mugabe is a despot and Israel's occupation an outrage - but the question mark hanging over the motivation of the proponent inevitably taints the pronouncement.

The conflation of Judaism and Israel - as though they are interchangeable - prompts a spiral of mutual recrimination. Israeli hawks and Zionist hardliners brand any criticism of Israel anti- semitic, regardless of its merits. Their accusations become so frequent that the term becomes devalued. Then Israel's detractors dismiss every allegation of anti-semitism, regardless of its merits, as a cynical attempt to stifle legitimate dissent. And so it goes on, until what should be a complex debate descends into polarised positions - "Zionism is racism" on the one hand, "anti-Zionism is anti-semitism" on the other.

Zionism is a political position, not a genetic given. It did not always command majority support among Jews. The minority of Jews who are anti-Zionist today might be accused of being psychologically unstable "self-haters", but the Board of Deputies of British Jews did not have a Zionist majority until 1939. Nor has Zionism ever held a monopoly on Jewish thought here. According to a poll by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, about 20% of British Jews surveyed in 1995 said they had negative feelings towards Israel (3%) or none at all (16%). But Israel nonetheless commands the affection of the vast majority of Jews in Britain.

That doesn't mean that gentiles have to support Zionism or Israel just because most Jews do. But it does mean that they cannot simply dismiss Zionism if they are at all interested in entering into any meaningful dialogue with the Jewish community. And it means that they have to be sensitive to why Jews support Israel in order to influence their views. To deny this is to maintain that it is irrelevant what Jews think. It is to move to a political place where Jews do not matter - a direction which they will understandably not follow, because they were herded there before and almost extinguished as a people. To declare "Zionism is racism" offers little in terms of understanding racism, anti-semitism or the Middle East. It is not a route map to debate, liberation or resistance but a cul-de-sac.

The same can be said for its opposite: "Anti-Zionism is anti-semitism". Anti-Zionism, up to and including opposition to the existence of the state of Israel, is a legitimate political position, with roots in the Jewish and non-Jewish communities. That does not mean that Jews have to support it. But to equate it with bigotry is unsustainable. "It is easy to forget that Zionism and the possibility of a sovereign Jewish state were once deeply divisive issues in Jewish life in this country," according to a 1997 Institute of Jewish Policy Research document on the attachment of British Jews to Israel.

Such engagement will not be easy, for the semantic differences reflect fundamental disagreements. But if it cannot be achieved in Britain, what hope is there for the Middle East?