A few days before the 2015 general election, the prime minister, David Cameron, tweeted: “Britain faces an inescapable choice – strong and stable government with me, or chaos with Ed Miliband.” Cameron won (the first general election the Tories have won outright since 1992), followed through on his pledge to hold a referendum on staying in the European Union, promised not to resign if he lost, lost and then resigned as chaos ensued.

Theresa May took over after all other challengers either fell on their swords, stabbed each other in the back, or put their foot in their mouths. It is as good a time as any to recall that, of all the jokers and hucksters standing for the Conservative party leadership, she was probably the best candidate. It really could have been worse. It could have been Andrea Leadsom.

May insisted she would not call a snap election, called a snap election promising strong and stable government, lost her majority, and has presided over a weak and unstable government. Her sole achievement has been to negotiate a deal with the EU that has twice been overwhelmingly rejected in parliament. Yesterday she presented her party with an ultimatum: if it accepts the deal it doesn’t want, it can get rid of the leader it doesn’t like.

Depending on the interpretation of a 415-year-old precedent by the House Speaker, John Bercow, and some procedural shenanigans, this may be how our trading and political relationship with Europe is settled: we are not so much leaving the EU as falling out head first.

Yesterday’s events in parliament illustrated four things about our politics and the Brexit process that are now unavoidable. The first, and most evident, is that the Conservative party is not fit to govern. Let us leave aside for a moment its mendacious policies that pauperise the vulnerable and deport the eligible. Morally its agenda is contemptible; and from Windrush to trains to universal credit its incompetence is undeniable.

But even if the Conservatives were decent and effective, as a simple matter of capacity they are no longer even low-functioning – they are not viable. Terrified of their own members and overwhelmed with internal rivalry, they cannot run themselves let alone the country. Their divisions are multiple and irreconcilable. (True, many say the same about Labour. But there are two important distinctions: Labour did not get us into this mess; and it has a far more plausible plan to get us out of it.)

The Tories lack discipline, direction, cohesion, coherence, substance, stature and credibility. They haven’t got a clue and they have no idea how to get one. With May’s promised resignation we will see the baton yet again pass from one failure to the next, each abdicating responsibility for the legacy they bequeath, none claiming ownership for the calamity they have wrought.

This is not just a question of politics, but personnel. Take a look at those poised with indecent haste to replace May, and it is clear what a shallow and shabby bench they are drawing from. A contest in which Michael Gove is favourite, and Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt are being seriously considered, owes more to reality TV than a party that wants to run the country with any serious intent. Things could get worse.

Second, we now have to have a second referendum. I have come to that conclusion belatedly and reluctantly. The first referendum was a mistake. But you can’t just support outcomes when they support you. Remain lost. There is a contemptuous sense of entitlement and condescension among a hard core of remain advocates that is not only deeply problematic but utterly counter-productive. That said, a narrow majority for a notion is not the same as a mandate for a plan: we voted to leave, and nearly three years later we clearly don’t know how.

Parliament has voted no to all the proposals it put before itself. We could wait until a little longer: there’s a chance MPs will support a customs union or May will somehow squeeze her deal through on the third attempt. But whatever passes will likely do so by a narrow margin, and that is partly how we got here. We’re imploding under the weight of our ambivalence. There is no guarantee a second referendum will produce a clearer result, but at least that will be on us, and we will be voting in full knowledge of what we are up against.

We need a general election. This is no longer a purely partisan point made in the the hope of a Labour government

Third, we need a general election. This is no longer a purely partisan point made in the hope of a Labour government. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. For the sake of our hospitals, schools and welfare alone Britain needs Labour in power. But the necessity of an election now transcends party advantage. As a practical matter this parliament is not working. Between Tory dysfunction, Labour feuds, Independent Group defections, Democratic Unionist party dependence and Sinn Féin abstention, it is incapable of taking on or seeing through not just a challenge like Brexit, but pretty much anything of substance.

As we saw this week, the numbers just aren’t there. A change in Tory leader alone is not going to solve that, indeed if anything it’ll make it worse. We need a national debate about the future direction of our country that goes beyond Brexit, while addressing many of the things that made Brexit possible – that is what general elections are for. Once again, that doesn’t guarantee a result one way or another – the polls are close and the moment is volatile – but it puts the decision back to the country as a whole.

Finally, we need electoral reform. The referendum nobody’s talking about that could have obviated both Brexit and the stasis that has followed was the 2011 vote that rejected the alternative vote system. It is thanks to first-past-the-post that, with 37% of the vote, Cameron was able to inflict the Tory psychodrama of Brexit on the rest of the country. It is why today the numbers in parliament aren’t there – we keep counting the votes the wrong way.

The claim for a winner-takes-all system is that it produces strong one-party government. It was always debatable whether that was desirable. It’s no longer debatable whether that is true. It’s clearly not. The real divisions we have in the country are compounded by our electoral system, which simultaneously produces governments and parliaments that are incapable of tackling them. Our destiny should not be shaped by the Speaker reaching back to before the Mayflower set sail for a ruling on how we can and can’t vote, regardless of what you make of the ruling.

We have a party that is not fit to govern, leading a parliament that is not able to legislate, elected by a system that is not fit for purpose. Yesterday showed that these contradictions are no longer sustainable.

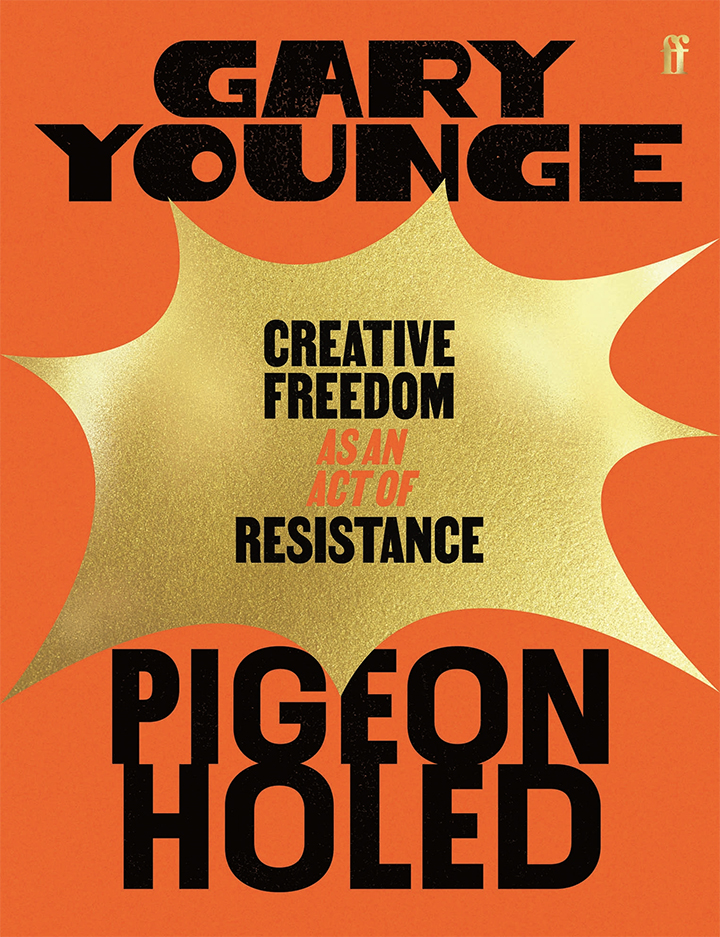

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist