We were told coronavirus didn’t discriminate, but it didn’t need to – society had already done that for us. But there is a path to a fairer future if we want it

In June 2020, I attended a Black Lives Matter demonstration in north London, not far from my house. My wife had found out about it from friends who’d found out about it on Facebook. We took the kids. Well over 1,000 people went; beyond my immediate circle, I only recognised a few there. The soundsystem was poor and I couldn’t hear what was being said from the stage. We took a knee like Colin Kaepernick while raising a fist like the Black Panthers and held the pose for eight minutes – the length of time Derek Chauvin kept his knee on George Floyd’s neck. Then we clapped, chatted and made our way back to our locked-down homes. I have no idea who called the demonstration. It just happened and then it was gone.

In the weeks before and after, institutions made statements; reviews were announced; social media avatars changed; museums reconsidered their inventory; Labour-led town halls went purple; curricula were revised; statues came down. Overnight, bestseller booklists were filled with anti-racist manuals and explorations of whiteness. This was the virus within the virus: a strain of anti-racist consciousness that spread through the globe with great speed, prompted by a video that had gone viral. Not everybody caught it, but everybody was aware of it, and most were, in some way, affected by it.

All of this happened spontaneously. Like oil waiting for a spark, a dormant constituency of like-minded people were ignited. Whether they were people who had thought a great deal about racism but had found no meaningful way to intervene on the issue, or whether they had been converted from ambivalence to passion by the single event of George Floyd’s death is not known. They were roused and found each other, just like we had that day in London.

It felt new, though nothing new had happened. The lived experience of racism for non-white people remains pervasive and unrelenting. A YouGov poll of ethnic minorities in Britain taken that same month revealed that a quarter have been racially abused multiple times, while almost half said their career development has been affected by their race. The polling showed significant differences between ethnic groups, as one might expect, but the broad thrust of the findings were similar for all of them.

In the US, the sight of Floyd being killed in real time was shocking, but news of it was not. The number of Black people being killed by the police in the US has remained fairly constant over the past five years. When the focus shifted from the US to domestic inequalities in Britain and elsewhere, it became clear that here, too, there were no specific new grievances. We were not protesting against some new manifestation of racism in Britain, but the enduring nature of it. The YouGov poll from June revealed the percentage of non-white people who think racism was present in society 30 years ago is virtually identical to the proportion who think it is present today.

No single organisation spearheaded the mass protests that sprang up around Britain. The groups that had been doing anti-racist work over the years sought to catch up with the new mood. But this was not a moment of their making. People came to Black Lives Matter as though gathering under a floating signifier. There was no Black Lives Matter office or official. There were several groups who adopted the name; none counted more than a couple of dozen participants. Each drew on the energy that was generated around them; each went in their own direction.

Given that they were small, varied and mostly new, there was no representative entity to make concrete demands. But then, when it came to race, Britain was not short of demands. There had already been the 2017 Lammy Review (on racial disparities in the criminal justice system), the 2017 McGregor-Smith review (on race in the workplace), and the 2019 Timpson Review (on school exclusions). All of these were commissioned by the government; to date, none of the key recommendations have been implemented.

Neither the problems that had sparked this conflagration, nor the solutions that might solve them were new, either. Stephen Lawrence would have been 45 when these demonstrations took place. The previous three years had seen the Windrush Scandal and Grenfell. Little had changed, apart from the urgent realisation that so little had changed for so many for so long.

The broadly positive response to the demonstrations was an indication that there was sufficient public support to, at least, embark on the kind of changes necessary. But the lack of real backing in parliament, and the absence of institutions that could force politicians to address longstanding racial inequalities, left little prospect of these changes actually happening. To shift that narrative, and avoid being constantly deflected by someone else’s agenda, non-white communities will have to write our own story.

Evidence for the impact of British racism was mounting, in mortuaries and hospital beds, even as the demonstrations took place. The pandemic laid bare the structural inequalities with which we had all become familiar, and to which we had then become inured. The first 10 doctors to die from Covid were all non-white. “At face value, it seems hard to see how this can be random,” the head of the British Medical Association, Dr Chaand Nagpaul, said in early April. “This has to be addressed – the government must act now.”

The government did not act. The inequalities became more evident. In England, mortality rates among some Black and Asian groups were between 2.5 and 4.3 times higher than among white groups, when all other factors were accounted for.

There are good reasons why minorities would find themselves disproportionately affected. Black and Asian people are considerably more likely to live in deprived neighbourhoods, in overcrowded housing, experience higher unemployment, higher poverty and lower incomes, than white people. That means that during the pandemic they have been more likely to have to go to work, use public transport and live in multigenerational homes, and less likely to be able to effectively self-isolate. They have also been more likely to be in the kinds of jobs that demanded contact with the public, such as nursing, working in care homes, taxi driving, security and deliveries.

If ever there was an illustration of how the inequalities of race and class work together, this was it. Minorities were not more susceptible because they were Black or brown, but because they were more likely to be poor. Office for National Statistics data shows that those who live in deprived areas in England and Wales were around twice as likely to die after contracting Covid. Most of the people who live in those areas are white, but non-white people are considerably overrepresented. But the reason they are disproportionately poor is, in no small part, because they are Black and brown. The virus does not discriminate on grounds of race. It didn’t need to. Society had done that already.

This presented a gruesome, if important, opportunity. For at the very moment when the nation’s consciousness was raised to the issue of racism through Black Lives Matter, we were presented with a clear example of how racism operates through Covid. Notwithstanding the handful of cases where non-white people were spat at, sometimes while being showered with racial epithets, there is no suggestion that anyone tried to deliberately make them ill with Covid. In other words, they were not disproportionately affected because individual people with bad attitudes did bad things to them. Their propensity to succumb to the virus wasn’t primarily the result of people’s uncouth behaviour, bad manners, mean spirits, crude epithets or poor education. For while all of those things are present, it is the systemic nature of racism that gives it its power and endurance.

Bequeathed through history, embedded within our institutions and entrenched in our political economy, racism is sustained as much, if not more, by compliance than intent. Take the Windrush scandal. The hostile environment policies announced by the coalition government in 2012 were not intended to ensnare people of Caribbean heritage who had been here for years. But the policies that demanded that landlords, employers and benefit agencies become border guards, checking people’s citizenship and right-to-work credentials, put the burden on some of the most economically vulnerable citizens to prove they were not illegal immigrants.

Michael Brathwaite, for example, had worked as a special needs teacher at a primary school in London for 15 years when a new HR department demanded a biometric card or passport to show that he was eligible to work in the UK. When he couldn’t produce one – he was a citizen and didn’t need one – he was summoned to a meeting with HR, his head teacher and his union rep.

“I was told that if I didn’t have a biometric card I couldn’t keep my job,” he recalled. “There was no kind of compassion towards who I am as an individual. That was the confusing thing, because I’d done nothing wrong – I was doing a fantastic job.” The London school where Brathwaite taught was listed outstanding by Ofsted: for almost half the children there, English is not their first language. It proudly celebrates Black History Month.

I daresay all the people at that meeting in which he was fired had done racism sensitivity training at some point, and had sound, respectful relationships with non-white colleagues and parents elsewhere. Some of them might even have been Black. They needn’t have been personally hostile towards Black people or immigrants. The system was already hostile. All they had to do was comply with it. (I am often invited to give paid talks about race and racism and asked to produce my passport before I can be paid.)

This is the system that left non-white people more vulnerable to Covid, and less able to survive it. In marked contrast to the brutality of the murder of George Floyd, Covid illustrated the banality of societal inequalities: the familiar, quotidian, bureaucratic complicity that results in far more deaths, even if they are far less dramatic.

Britain was nowhere near reaching this conclusion in the wake of Black Lives Matter. The political education spawned by the protests had been limited. The anti-racist sentiment it had unleashed was broad but shallow. Nonetheless, a critical mass of people was primed for the conversation that had been set in motion. A dynamic had emerged in which a significant number of non-white people felt emboldened to challenge the racism that they witnessed and experienced, while white people’s awareness was heightened and therefore they grew more receptive to the urgency and veracity of these challenges.

The evidence for this is partly anecdotal. Virtually everyone I know had some kind of meeting or interaction at their work that they considered in some way substantial. I got the impression that some of these engagements were quite uncomfortable, and productive – some colleagues talking candidly about how they felt while others listened, maybe for the first time, aware that they were implicated in whatever changes were necessary. Meanwhile, my inbox filled with invitations to talk to industry groups, staff networks and trade unions about how they might adapt. Neither my friendship circle nor my inbox are remotely representative. But they are indicative, at the very least, of the changes in the world immediately beyond me.

Elsewhere, there was evidence that things in the country were shifting. An Ipsos Mori poll from May 2021 showed that more than half of British people think we need to do more to tackle racism, against just 13% who think we are doing too much. In August, significantly more than half saw taking the knee as very important in tackling racism in football; in March it was barely over a quarter. Another YouGov poll, taken after the Euros final, showed that a third of people who previously did not think racism was a problem in football now do.

There has, of course, been considerable resistance to this progress. The eruption of Black Lives Matter had predictably been misrepresented and distorted by the media, while the notion of systemic racism went either unreported, misreported or unexplained. Those for whom these debates, about systemic racism and the legacy of colonialism, were new may have found it disorienting – like walking into a movie halfway through to witness a car chase and struggling to work out who is pursuing whom and why.

An Ipsos Mori survey conducted in July 2021, a year or so after the wave of BLM protests, revealed that while more than two-thirds of the country has heard of the terms “systemic racism” and “institutional racism”, still half did not have a good understanding of them. A YouGov poll from shortly before Floyd’s death showed that one in three Britons believe the empire is something to be proud, of and one in five think it’s something to be ashamed of. In 1951, the UK government’s social survey revealed that nearly three-fifths of respondents could not name a single British colony. “The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side,” George Orwell once wrote. “He has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.”

But there is far more active hostility, too. Racially motivated hate crimes in England and Wales rose 12% in the first year of the pandemic, continuing a sharp trend upwards over the last five years. Neo-Nazi demonstrations around statues, booing the national team when they take the knee, mobilising to take control of the National Trust governing council to prevent further reckoning with its colonial and slave-sponsored inventory – all these things point to considerable hostility. We should not be too surprised by this. Where there is racism, we must assume there are racists; and when racism is being fought, we must assume the racists will fight back. However, while their attitudes are hardening, it does not appear that their numbers are growing.

We don’t know if these shifts in public opinion are sustainable. Racism is itself a hardy virus that adapts to the body politic in which it finds a home, developing new and ever more potent strains. But if they are lasting, then that is a significant achievement. It is possible to change laws and practices without changing people’s minds, but then those legal advances are vulnerable to backlash and repeal. By changing people’s minds, you change the culture and lay the groundwork for significant changes in policy for the future, as well as for a new consensus. Dams may break, as they did over gay marriage. This is not a zero-sum game, in which you either change minds or laws – the two are symbiotic. But what you cannot do is dismiss one as irrelevant and the other as paramount.

If the potential of anti-racism became evident in this moment, so did its precarity. There are three main reasons why the lessons that emerged from Covid in the wake of Black Lives Matter might not be heeded. The first is that while, in the population at large, there there is a clear political constituency for this journey, there is little political will in parliament.

When the protests occurred, the Labour party, nationally, resorted to its historical default position of condemning racism but failing to embrace anti-racism as its antidote, leaving bigotry deplored but never challenged. It is apparently incapable of framing anti-racism in terms of class solidarity, or of asserting that British history contains atrocities as well as achievements. So when anti-racist protests do emerge, and even when they’re peaceful, Labour leaders keep their distance for fear of alienating white voters. In this regard Keir Starmer is archetypal. England’s football manager, Gareth Southgate, showed more leadership and took more risks on the issue – backing the England players taking the knee and eloquently explaining why – than Starmer ever did. In practice, the Labour position has been to agree that Covid exposed structural racial inequalities, while being ambivalent about the protests that were trying to address them, and failing to come up with a coherent plan for tackling them.

The Conservative government took the easier, if more implausible route, of denying any significant racial component to Covid outcomes. When presented with evidence, often from its own reports, that suggested otherwise, it basically said that while it was not sure how to explain the racial discrepancy, it wasn’t structural racism.

Factors such as housing and jobs were more significant, government representatives claimed, and there were greater discrepancies, such as age. This merely proved that the government understood neither its own reports nor what structural racism actually meant. Almost all the studies on racial inequalities had already taken age and other factors into account. And the government referred to the fact that minorities were concentrated in the kind of jobs and housing that made them more vulnerable, as though it were mere coincidence.

This combination of sloppy reasoning, inadequate attention to detail, toxic messaging and sophistry was emblematic of the government’s interventions on race during this time. The fact that all this came from the most racially diverse cabinet ever seen in the UK simply illustrated the limitations of symbolic representation. If you focus, as many liberals do, on organisations looking different, even as they act the same, you end up not with equal opportunities, but photo opportunities. It’s a form of diversity that Angela Davis once explained to me as: “The difference that brings no difference and the change that brings no change.”

The equalities minister, Kemi Badenoch, a British-born woman of Nigerian parentage, is a case in point. She has publicly attacked two young Black female journalists, one for asking her straightforward questions, the other for doing a story she disapproved of. In an interview with the Spectator, she lamented the “boom in sales” of books like Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. “Many of these books – and, in fact, some of the authors and proponents of critical race theory – actually want a segregated society,” she said.

They don’t. But this wasn’t just a statement in bad faith. It was bad politics. Just a few months earlier, after the protests erupted, Eddo-Lodge’s book topped the UK book charts – the first time a Black author had done so. Badenoch was not just complaining that the book was written, but that it was popular.

This was just one example of how the government in general, and Badenoch in particular, might have been out of touch with the public mood. The Sewell report was another. Chaired by Dr Tony Sewell at the head of a non-white group commissioned to investigate racial and ethnic disparities following the Black Lives Matter protests, it found only “anecdotal evidence of racism”, but claimed it could “no longer see a Britain where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities”. Poorly researched, badly argued and academically illiterate, it failed on its own terms of producing a credible rightwing intervention into the nation’s race debate.

The point here is not that their argument failed to take into account the relevant academic literature and practitioners’ expertise, or to pull together a coherent response to the protests – it wasn’t intended to. Sewell already had a history of downplaying the existence of institutional racism, and assembled the group in his own ideological image. The problem was that, despite significant promotion in the media, the insistence that Britain was a racial success story failed to chime either with non-white people’s lived experience or most white people’s perceptions. Seventy-one per cent of people said that either they had never heard of the Sewell report, or knew little about it. Of those who had heard of it, only a quarter had a favourable opinion of it. First condemned, then derided and ultimately discredited, it did not shift the race debate in Britain, but went largely ignored by all but those who held firmly to those views before it was written, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

The question of how we leverage the urgency and clarity of this moment to effect real and lasting change is a crucial one, which brings us back to that day in north London over a year ago. Nobody took our names; there is no way to reconvene that group. Its effect was powerful for those who were there, but fleeting.

The absence of structures or identifiable leaders in social movements has its benefits – it enables them to act quickly and allows new, young (often female) leaders to emerge who have previously been marginalised. But it can also mean a lack of democracy, clear direction, consistency or permanence.

The US has long-established Black-led institutions – such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, historically Black colleges, the African Methodist Episcopal church, and so on – which, for all their problems, can nurture, incubate and sustain these moments. In Britain, no such longstanding organisations exist. When it comes to activism, these deficits are not specific to anti-racism or Black Lives Matter. It reflects the nature of modern, progressive social movements, from occupy Wall Street to #MeToo. Each one mobilised and energised large groups of people, transformed the political conversation and laid out alternative visions for how the world might be understood. That is no small thing.

But they created space they cannot hold. After each surge, we are left waiting for the next sight of oil on the ground. We are at the mercy of spontaneous events that arise from structural inequalities and inequities.

Institutions offer the possibility of elaborating a coherent strategy on their own terms, rather than being buffeted by any and every incident that occurs. There are moments when Britain appears engaged not so much in a debate about racism as a litany of race-based tantrums: a media figure or politician says something reprehensible, prompting an outcry that in turn prompts an outcry about the outcry. Terms such as “woke” and “culture war”, deprived of any meaning they once may have had, are tossed around like confetti.

“The very serious function of racism is distraction,” Toni Morrison argued in 1975. “It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend 20 years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

There have been many things recently. The attacks on Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, and on the Euro 2020 penalty takers, racism in the Yorkshire cricket board, the Sewell report. All of them are serious and important, though not all equally so. Each of them might, and usually do, reflect elements of what might be a broader agenda. But in the absence of a defined agenda, we end up being dragged into a “debate” about something Piers Morgan said, or colourism within the royal family.

The comprehensive and coherent response needed to combat the inequalities revealed through the Covid pandemic cannot be left to happenstance.

We should continue to demand that the government conduct a review into the racial disparities exposed and exacerbated by Covid. But we should hold out no expectations that they will do so, and none that they will do so intelligently, in good faith. Nor should we expect much from Labour. They are not likely to be in power for some time, are more engaged in fighting among themselves than injustice in any case, and appear to be moving away from, not towards, the kind of structural changes we would need.

The point is how to channel that pressure, and then apply it. Here we have something of a precedent. Starting in 2018, the Guardian reported cases about British citizens being threatened with deportation, stripped of access to housing, health, employment and benefits for several months before it became known as the Windrush scandal and cost a minister her job. The government was shamed into committing itself to finding out what had gone wrong and setting up a review. Once the pressure was off, its attention waned. But the review, overseen by Wendy Williams, continued. In several cities across the country, there were public meetings. I attended one in a church hall in Bristol, where local people spoke about their experiences.

One man had come to Britain from Jamaica with his parents when he was a baby. He applied for a driving licence, but was denied it because he couldn’t prove he was British. “I contacted my MP and they said it sounded like an immigration issue,” he said. “And I thought, how could it be, when I’ve never been out of the country?” Another had come aged 13, also from Jamaica, and had been here for 50 years – he has great-grandchildren here. After undergoing a mental health crisis, he had ended up in prison on remand. The charges were later dropped, but his time in prison meant his application for citizenship was denied.

Williams wrote her report with important recommendations. We wait to see if it will be heeded. Given that only 5% of the Windrush victims have been compensated so far, we should not hold our breath. But nor should that prevent us from learning some lessons.

Here is my proposal. We should do this again; only without the Home Office. We could hold a series of themed public meetings, independent of political parties, across England, on a range of issues, at which a few experts and practitioners in each field could lay out the challenges and then open the floor for people to bear witness (race in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has its own dynamics, and will need specific proposals). Go back to Bristol, for example, to do a session on education. Have David Olusoga, who lives there, talk briefly about what changes he’d like to see in the curriculum; a local teacher talk about the challenges she sees in the classroom, and a parent-governor share their experiences: then have the audience talk about what they have seen and what they would like to see. The review would then go to Leicester, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool, Bradford, Oldham, London, Luton (to name but a few), and in each place health, policing, arts, youth, crime, housing, immigration or employment (among other things) would be discussed. Standing somewhere between a citizens’ assembly and a truth-and-reconciliation event, the evidence could then be collected and a report written reflecting the needs and interests of participants.

The aim would be threefold. First to hear, at a local level, what works and what doesn’t when it comes to addressing racial disadvantage, and hopefully develop solutions that people own and can organise around. Second, to listen, be heard, bear witness and testify, shifting the emphasis from an inhuman system to the human consequences of that system. Third, to create the kind of mediated event that might engage a broader public about the challenges, remedies and obstacles to tackling systemic racism.

There is no shortage of expertise in the community that might be leveraged to make these high-profile, well attended events. Steve McQueen might document it; Charlene White or Samira Ahmed might moderate it; Eddo-Lodge, Nesrine Malik or Sathnam Sanghera might write it through.

Following the Windrush review session in Bristol, I wrote: “Were it not for the fact that the participants need the option of anonymity, the hearings should be televised. For it is in the unmediated bearing of witness of these Britons that the human cost of a malicious immigration policy might be more fully understood. It should be televised because the people who need to see it – those for whom immigrants are faceless, threatening figures without family, ambition or story – were not there.”

The perils in this plan for public meetings about Covid and racism are manifold. Nobody might show up; worse still, loud mouths, disruptors and control freaks might show up; it could descend into chaos or banality. If it is effective, then efforts to undermine it will be intense. And, of course, its weakness lies in the very reason why we need it, because in the absence of institutions we have been unable to formulate an agenda. Who will decide where, when, what and whom are questions that all offer opportunities to bicker, blunder and ultimately blow it.

No single event, or series of events, will remake a system centuries in the making, so ingrained that many do not even recognise it as a system at all. But such an initiative would be an attempt to convene in person, not just to protest, but to plan and ultimately strategise. To root the discussion and consequent intervention in the needs of communities most affected, rather than at the mercy of whatever happens next. So that we might meet deliberately. Take each other’s names. And build something on our own terms.

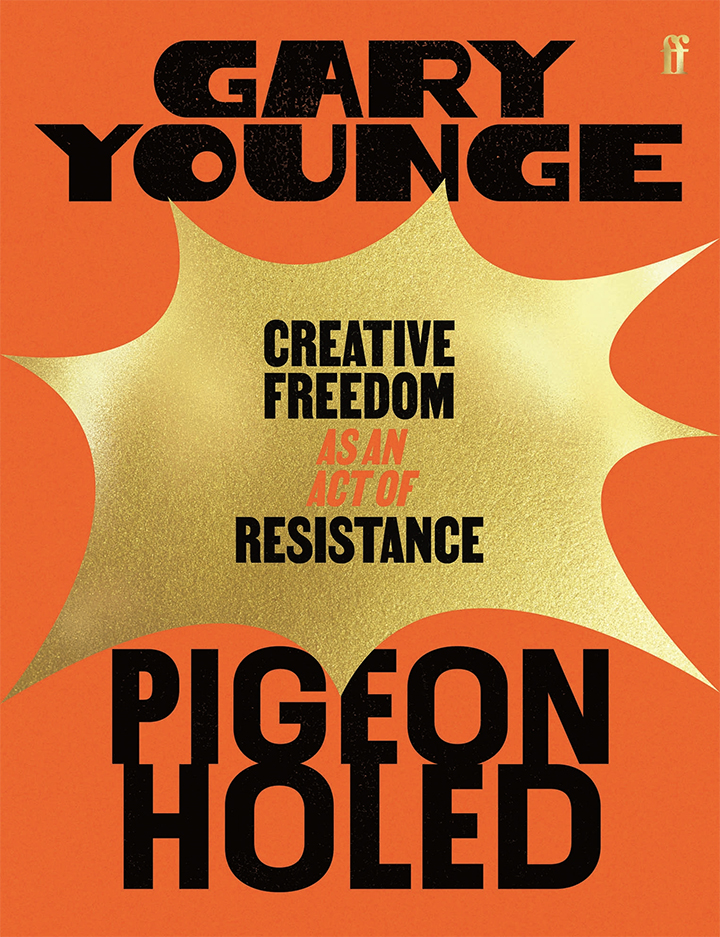

Gary Younge is a professor of sociology at the University of Manchester