On the evening of November 22, 2013, as the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination drew to a close, Kenneth Mills Tucker, 19, sent a tweet letting the world know his plans for the night: “Out with the gang Dooney Wayne n Rell what’s going on tonight. My last weekend being a teenager.” It was to be Kenneth’s last weekend ever.

Shortly after 3

on November 23, a residential area of northwest Indianapolis crackled with gunfire from an automatic weapon, sending stray bullets through windows. By the time the police arrived, the scene looked like something from a David Lynch movie. A green 2002 Honda Accord had struck a utility pylon and flipped onto its roof. Of the four passengers, one had fled, two sat on a grass verge complaining of pain, and the last—Kenneth—lay motionless, having staggered about 100 feet from the car with a bullet in the left side of his torso. At 3:57

, as the coroner noted, “Medical intervention was unsuccessful and the decedent was pronounced non-viable.”

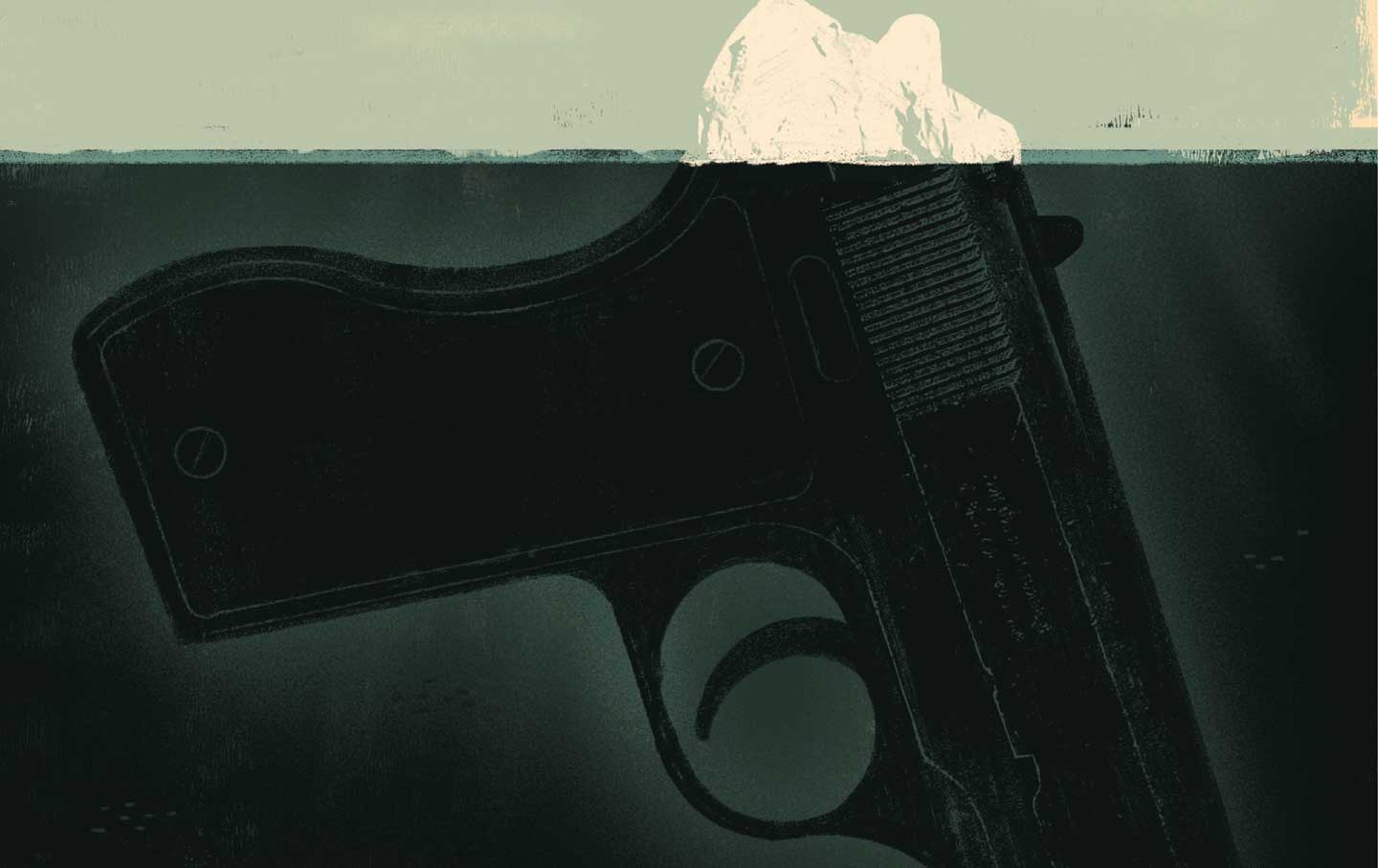

November 23, 2013, came in the months between George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the death of Trayvon Martin, when the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was coined, and Michael Brown’s fatal shooting by police in Ferguson, which was when the hashtag really took off. It was an unremarkable Saturday shortly before Thanksgiving—and as befits an unremarkable Saturday in America, 10 children and teens were shot dead. (On average, seven children are killed by guns in the United States each day, but weekends tend to be worse.)

This was the day I had picked at random to put a human face—a child’s face—on gun violence. Black, white, and Latino, over a 24-hour period, these children fell in barrios, suburbs, and rural areas; on stairwells, on street corners, and at sleepovers. All were boys: The youngest was 9 and the oldest was Kenneth, who was the second to be shot and the first to die. I spent 18 months looking for their families, friends, teachers, and coaches—anyone who knew them. By the time I completed the project, two things—beyond the personal stories—became clear.

The first was that every black parent I spoke to said that they had assumed this could happen to their son. (Of the 10 children who were killed that day, seven were black, two Latino, and one white; on an average day, five would have been white, four black, and one Latino.) “You wouldn’t really be doing your job as a parent here if you didn’t think it could happen,” one father in Newark told me. His son was shot dead on the evening of November 23. A mother in Dallas whose son was also shot that evening had assumed that her other son would be the one to get killed—but either way, she’d factored it in. In low-income communities of color, death stalks youth with relentless intent. Most of the teenagers I met who were friends of the deceased knew others who’d died; their Facebook pages and Twitter accounts are like online graveyards.