A US president with no moral authority flies in to meet a British prime minister with no authority whatsoever. Each seeking legitimacy in the presence of the other, they hail their special relationship like two bald men might brandish a comb. Isolated in their trajectories, belligerent in their rhetoric, incoherent in their policies, they have alienated their allies in pursuit of a brazen nationalism that bodes ill for them and everybody else.

Donald Trump’s diplomatic needs are significant. He left America having escalated a trade war with China and stopped off at Nato in Brussels where he insulted everybody, openly questioning the purpose of the bloc of which the US is ostensibly the cornerstone.

America needs a friend. The soft power on which the nation once thrived – the broad cultural appeal of its actors, musicians and authors that drew in even those who abhorred its foreign policy – is steadily being extinguished by Trump’s heinous political leadership. He may not know how to make friends, keep them or treat them, but he needs them all the same.

Whether you are joining a planned demonstration or marking Trump’s UK visit in some other way, share your story and photographs via our dedicated callout here.

You can also share your stories, photos and videos with the Guardian via WhatsApp by adding the contact +44(0)7867825056

Your responses will only be seen by the Guardian and we’ll feature some of your contributions in our reporting. You can read terms of service here.

Fortunately – for him, if not for us in Britain – he has found here the only kind of friend he could tolerate: one who is craven, compliant and desperate. This obsequious understanding is not new. It is the product of a post-colonial fantasy that Britain’s global role would be to provide a diplomatic bridge across the Atlantic, as the sole reliable conduit between Europe and America.

While Americans have episodically found this devotion convenient, in reality the “special relationship” has only ever really been “special” for Britain. But now America has become unhinged and Brexit has in effect made us a bridge to nowhere, it’s difficult to see what’s in it for anybody. His arrival on the day the government published its Brexit white paper, based on last week’s Chequers agreement, makes this only too obvious.

Last week Theresa May announced her plans for the next phase of Brexit negotiations, and these were greeted with howls of betrayal by grassroots Tories and their representatives. Collective cabinet discipline barely survived the weekend. When Boris Johnson’s resignation as foreign secretary followed that of David Davis as Brexit secretary, May seemed to be in peril.

Johnson did not resign as a matter of principle. Having described the Chequers agreement as “polishing a turd” he first agreed to help shine it up, only to resign a few days later after he sensed May’s vulnerability. Ambitious to a fault, he has not stepped down so he can pursue an honourable cause from the backbenches; it is now only a matter of time before he challenges May.

Since she is permanently vulnerable, that could be any time. It is now clear that the no-confidence vote threatened by the hardcore Brexiteers was more bark than bite. When finally put to the test it transpired that the plotters’ bench was too thin, their numbers too few and their spirit too pusillanimous to pull it off – for now.

Those who claim that the absence of an uprising at this point has put May in control mistake survival for strength. Trump’s description earlier this week of the British government “in turmoil” was one of the rare accurate things he has said. The trouble is there has not been a moment since May became prime minister when that has not been true. She has survived. Indeed, the principal – if not sole – achievement of her tenure seems to be that she is still here.

But the threat still stands. Now that May has shown her hand and energised her enemies, the Tories have a problem similar to one Labour had – and in essence still has. The Conservative parliamentary party is seriously out of step with its base, which overwhelmingly voted for Brexit and appears (anecdotally, at least) to be unimpressed with the deal. Schisms as fundamental as this generally end with rupture or realignment, neither of which will end well for May.

The pressure points for rebellion will be many. The European Union welcomed the Chequers statement because it meant there was finally something to negotiate with the British government, as opposed to simply watching it negotiate endlessly and fruitlessly with itself. But much of what emerged from Chequers has either been rejected already by the EU, or is unlikely to be accepted. So if this level of compromise is treated as treachery by the Tory rank and file, the stages to come will only excite them further.

Neither Johnson nor Davis – nor any of the Brexiteers – have a plan that could actually work. Nothing that they promised was real, or true, or possible. Whether we remain or leave the EU, our sovereignty was always contingent on our presence within the global neoliberal system which operates according to the golden rule: those who have the gold make the rules. Both rhetorically and strategically, the Brexiteers have trapped themselves in the role of permanent defiance and disappointment. The world is not what they want it to be. In the absence of any strategy for bending it to their will, they would rather rail at it.

Yet however ridiculous they now seem, however fanciful, vain and pompous, they remain dangerous. For, as counterintuitive as it may appear, there is potency in this powerlessness. With sufficient encouragement, the rage it creates – the frustration it engenders, the nostalgia it spawns – can have a disruptive and corrosive impact on politics. We know this because we have seen it happen elsewhere, with disastrous consequences. We know this because these were the forces that made possible the president with no moral authority, and the prime minister with no authority whatsoever.

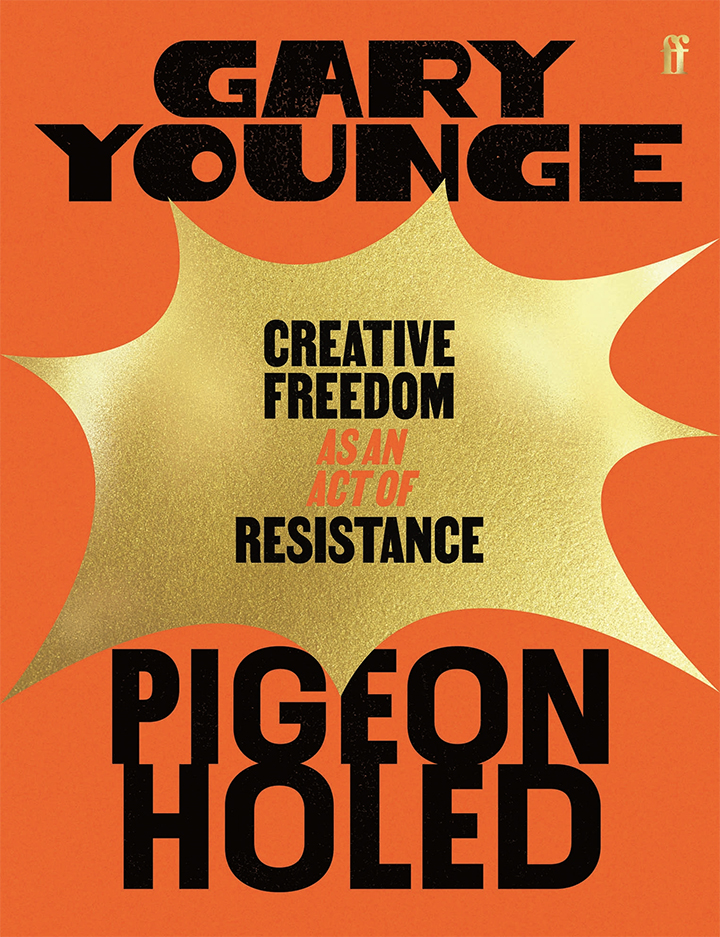

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist