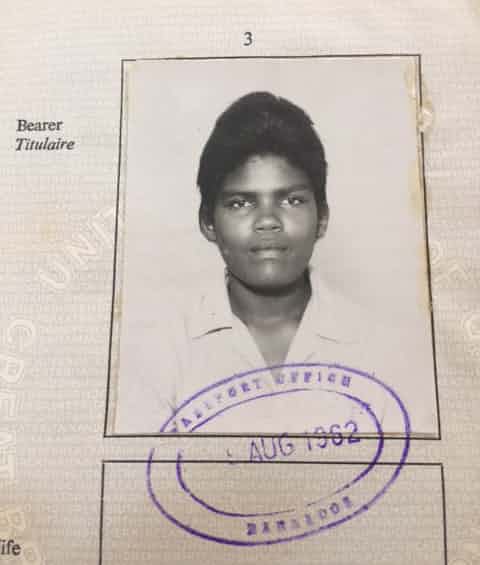

A few weeks ago, while looking for the family railcard, I found my mother’s first passport. It’s blue and hardbacked, with a lion and a unicorn perched on Latin and embossed in gold. The kind the Brexit types bang on about. The kind we will have when we get our country back. The ones that will be made in France.

Only mum’s was a bit different. For above the crest it says British Passport and below, in the same gold lettering, it reads Barbados. It was issued by the governor of Barbados “in the name of Her Majesty”, and cites her nationality as “British Subject: Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies”. Barbados did not gain independence until 1966. My mother didn’t cross the border to come to Britain – the border crossed her.

The black and white picture inside is of a teenager, just 19. High hopes, high cheeks and high hair, with dark skin against a crisp, white cotton blouse. On the penultimate page are the only two stamps. One, an entry certificate listing her as a student; the other from the immigration officer at Gatwick marked 20 August 1962 (a year later than I had previously thought).

She arrived four months after the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act – the first piece of legislation that sought to weaken ties and obligations with those whose colour was no longer deemed a good fit for the crest. The Labour leader at the time, Hugh Gaitskell (no radical he), branded it “cruel and brutal anti-colour legislation”.

Even as Britain started trying to keep black people out, it sent for my mother, her passage paid up-front with an agreement that she would pay it back later, because the country desperately needed nurses. And so, as was the case for all my aunts who settled here, that would be her job for more than a decade.

This summer will see the celebration of two 70th anniversaries – the creation of the National Health Service and the docking of the Empire Windrush, bringing with it the symbolic arrival of postwar migrants from the Caribbean.

The first will honour Britain’s most cherished institution. The NHS makes us more proud to be British than the monarchy, even as we are more dissatisfied than ever with the way it is run. If there must be patriotism – and for now it appears there must – then let it be for a collective institution set up to care for everyone, regardless of their ability to pay, and paid for by everyone who is able to contribute their taxes. For the second, the nation will throw its arms awkwardly around a group of people it has relatively recently decided to revere – older Caribbean migrants – even as it seeks to avoid any substantive discussion of another, albeit related group that we continue to revile – immigrants in general. Our bigotry is both selective and fickle, but no less passionately felt for that. We pride ourselves, simultaneously, on being both tolerant and hostile: those we deport today we may dedicate a commemorative day to tomorrow.

For the most part, these anniversaries will be marked separately – as though their age were the only thing they had in common. But we would grasp the historical importance and contemporary challenges of both much more clearly if we sought to understand them together, since their histories are intimately entwined.

The NHS, like so much of postwar Britain, was built by immigrants and could not have survived in its current form without them. There were recruitment campaigns for nurses in Malaysia, Mauritius and elsewhere in the empire as well as the Caribbean. By 1971, 12% of British nurses were Irish nationals. By the turn of the century, 73% of the GPs in Wales’s Rhondda valley and 71% in nearby Cynon valley were south Asian. Today, roughly a third of the tier-2 visas for skilled migrants go to NHS employees.

There is a certain civilising logic to this. For all the talk of national culture, ethnic diversity and racial difference, we are all human. As obvious as that may sound, (and when babies are being snatched from parents on America’s southern border or boats of refugees are being turned away from Italy the question of immigrants’ humanity has yet to be politically settled) it explains why health would be a sector that favours migration. The human body is the same the world over. Whatever sense of racial or national superiority one may harbour, it is likely to be tempered when the black foreigner in the white coat is the one charged with keeping you alive.

Nonetheless, there is a contradiction that must be confronted. The institution that we value the most has been sustained by people whom we value the least. Even as the Thatcher’s rhetoric about being “swamped” by people of a different culture gained traction British lives were, literally, being saved by professionals from the swamp. If Enoch Powell’s “rivers of blood” prophecy had ever become true, the victims would have been patched up by doctors from India and Pakistan whom he invited to the country several years earlier, when he was minister of health. No claim about the strain that immigrants place on the NHS can be taken seriously without a concomitant appreciation of the strain it would be under were it not for the immigrants working in it.

This is not a problem of the past. That fundamental inability to understand immigrants as people who stay and contribute, rather than as people who come and take, remains a central obstacle to any meaningful debate about immigration. Not only are we failing to have the discussion in terms of our human obligations; we are not even having it in the national interest.

In few places is this clearer than the NHS. According to an NHS Improvement report, in February this year 35,000 nurse vacancies and almost 10,000 doctor posts were unfilled. There has been a growing exodus of European nursing staff since the Brexit referendum. Yet earlier this month the Financial Times reported that 2,360 visa applications by doctors from outside the European Economic Area had been refused in a five-month period. Last week the shortage forced the Home Office to exempt medical professionals from the cap on skilled workers that was set by Theresa May several years earlier.

The outcry over the treatment of the Windrush generation last month shows that we are capable of both appreciating the contributions that immigrants make and protesting against the capricious and cruel state harassment that can be meted out to them. It has yet to fully sink in that what was wrong for the Windrush generation is wrong for all immigrants, and that when we argue for a more humane and less hostile environment for immigrants we do so not just for the sake of foreigners. We do it for ourselves. Our health depends on it. Seventy years after Windrush docked and the NHS was created, we should have learned by now. If we don’t watch out, our xenophobia will literally be the death of us.

Gary Younge will be talking on Windrush and the NHS at 70 at the Assembly Hall, Lambeth Town Hall in Brixton, London on Tuesday 26 June 19.30-21.30