They call it the “reachable” and the “teachable” moment: that brief window when a young person who has just been stabbed will be most receptive to a message about how to make changes in their life. Just as the most propitious time to talk to people about diet and exercise is when they’ve just had a heart attack, the best chance for this lesson is right after they turn up in hospital with a stab wound.

“When you say, ‘There’s a one in 100 chance of that happening to you,’ nobody thinks they are going to be the one,” says Dr Emer Sutherland, clinical director for emergency medicine at King’s College Hospital in south London. “But when you are the statistic, everything suddenly becomes relevant to you.”

So just upstairs from the accident and emergency ward at King’s is a team of youth workers, employed by a charity called Redthread. They are not doctors, but have been trained to work in a hospital environment and have access to young patients’ records. “I tell them I’m a youth worker,” says Lucy, who runs the unit at King’s. When she first meets a patient, she tells me, she starts by pointing to the doctors and nurses and saying: “These people will take care of you medically.” If the police are also there, she will say: “They will investigate the crime.” Then she describes what Redthread offers. “What I will do is all the other stuff. Think about where you’re going home to. Maybe you need help with housing, college or employment, or to process what has happened. Anything else that is outside of your body that you need, that’s me.”

“Often they will start off with the most urgent needs. Food. Drink,” Lucy explains. “I always feel it’s a test. They want you to do something practical for them. They might want a Lucozade. One guy wanted me to ring probation because he was worrying about a breach. I did that. Then he called probation to check that I’d done it. Once he realised I could deliver, he was cool.”

Not all of the young people engage. But most do. “When we can get to someone and talk face to face, especially if they stay overnight, then 80% of them want to have a conversation – but if they’ve left the hospital, only 40% answer the phone.” Redthread will help them with almost anything – from an outpatients’ letter to help with finding a new place to live, away from an area or a clique that is unsafe. “I tell them: ‘I don’t want to see you here again,’” Lucy says. “I don’t want to see you here until I’m holding the hand of your partner who’s having a baby.”

Redthread are treating more than just a stab wound. They are trying to tackle some of the conditions that made the stab wound possible. Earlier this year, a handful of fatal stabbings (and shootings) in London launched another one of Britain’s episodic fixations with knife crime and youth violence. In what is now a familiar cycle, headlines depicting the capital as a cesspit of murderous villainy provoke dramatic declarations from politicians, who respond to the coverage rather than the crime. With context scarce, and tales of human tragedy and incendiary predictions plentiful, a sense of moral panic burns brightly for a few weeks, and then fades as the news cycle moves on.

For the papers and politicians alike, hyperbole takes over where facts are absent – often mistaking London for all of Britain, and mistakenly assuming that race, not class, is the only common thread. At one stage, the news was dominated by the claim that London had a higher murder rate than New York, which was true if you counted February and March but not January, and ignored the fact that New York saw more than twice as many homicides as London the year before.

The tabloid depiction of London’s streets running with blood was also picked up by Donald Trump, in a desperate attempt to justify America’s lax gun laws. The fact is that a child or teenager was 16 times more likely to be shot dead in America in 2016 (the last year for which figures were available) than they were to be stabbed to death in Britain last year. For young people in London – which Trump likened to a “war zone” – fatal stabbings are 4.5 times less likely than shooting deaths across America. So in the toughest place in this country in one of the toughest years, British kids are safer than American kids in any year.

This is not to say that Britain – and particularly London – does not have a problem. A growing number of children carry knives, many to protect themselves, and a growing number are getting stabbed. Last year was the second worst in four decades for teenage knife deaths in London – and this year could be worse. But it’s still not even remotely the problem our leaders think it is. That much is clear in the way they talk about it.

Almost every time the term “knife crime” appeared in the national press last year – outside of this paper – it was referring to black kids in London. (There was one exception, for the death of Sait Mboob, a black 18-year-old stabbed in Manchester.) So the term is not used to describe all crimes committed with knives, just those where young black men in London are involved. Much like “mugging” once only denoted black street crime and “street grooming” only refers to Asian sexual predators, “knife crime” is a racialised construct.

Working on the assumption that gangs – another term generally reserved for black kids – are driving the rise in knife crime, politicians tend to call for stiffer sentences and tougher laws, and target cultural expressions most popular with black youth. In 2007, then prime minister Tony Blair told an audience in Cardiff: “We won’t stop this by pretending it isn’t young black kids doing it.” A year earlier, David Cameron, then the opposition leader, suggested in a speech that hip-hop was partly responsible for youth violence. “I would say to Radio 1, do you realise that some of the stuff you play on Saturday nights encourages people to carry guns and knives?” More recently, drill music in particular has come under scrutiny, with police blaming videos they claim are inciting violence on social media.

Almost everything about these assumptions is wrong. In a year-long series called Beyond the Blade, the Guardian gained access to previously unavailable data on young people and knife crime from the past 40 years, and counted all the children and teens killed by knives last year. We discovered that roughly half of all teenage knife deaths, on average, take place outside of London. The overwhelming majority of those killed by knives in Britain in the last 40 years are not black. The overwhelming majority of young people caught carrying knives today are not involved with gangs.

This matters because it makes it more difficult to tackle the issue when you consistently and persistently misidentify it. Treating knife attacks as a criminal issue that affects black kids in London removes the majority of young people who are fatally stabbed from the equation altogether. The longer sentences fill up jails; the stop and searches make it more difficult to build trust and cooperation where the police most need it; it makes people who aren’t black or living in London complacent that their children are not vulnerable.

Every stabbing is a crime. But the most effective way to deal with “knife crime” is to treat it as a public health issue, and to tackle all the contextual elements – housing, employment, mental health, addiction, abuse, as well as crime – that make some people and communities more vulnerable to it. But that would take public spending and a coordinated and compassionate strategy that focuses on it for the long term. The government has the capacity to do this, but there is no evidence yet that it has the will. It takes longer than a tabloid news cycle to see the patterns and engage with the people affected.

Near the end of the 12 years that I spent reporting in America, I wrote a book about gun crime, which told the stories of the 10 children and teens who were shot dead on a single day in November 2013. The aim was to humanise those involved and challenge prevailing assumptions by telling the stories behind the grim statistics.

When I moved back to London, a few people asked me if I would do something similar about Britain. I could not, I replied, because – thankfully – there just aren’t that many gun deaths here. But perhaps, some suggested, it would be possible to study knife crime over a much longer period than one day.

That was the genesis of this series, which has sought to track each individual death of a child or youth who had been stabbed – and, by telling their stories, to better understand the many issues and causes connected to knife crime. Thirty-nine children and teens were stabbed to death in 2017. The demographic breakdown of those young people might not challenge many stereotypes. With the exception of Matthew Cassidy, who was killed in Wales on 29 May, they all fell in England. Of the 39 cases of alleged stabbing, 22 were black, 14 were white and three were Asian. Twenty died in London, with the next-highest concentration being three in Manchester. The average age was 16. But the stories behind those deaths did confound the usual assumptions about knife crime. They died in all sorts of places, from rural Essex and Oxfordshire to the inner city; outside nightclubs and schools, and at an Eid celebration.

The youngest was Mia Kelly, who was just minutes old when her mother, Rachel Tunstill, stabbed her 14 times in the neck and back with a pair of scissors, in Burnley, one of two infanticides in 2017. After killing Mia, Tunstill wrapped her body in a carrier bag and put her in a bin, while her unsuspecting partner played Xbox in the next room.

Many of the children fell in clusters, which would in turn provoke those flurries of media interest, followed by protracted periods of relative calm and complacency. On 8 August, three young people died in one day. The five weeks and three days between 28 August and 5 October was the longest stretch in which no child was stabbed to death. That relative calm was breached on 6 October when two young men were killed within 24 hours.

In many of the stories, it was not clear what had led to the stabbing. Some succumbed to the pettiest of rivalries. Jordan Wright of Blackheath in London died after a WhatsApp altercation with his friend Paul Akinnuoye about who was more “gay”. (Social media can accelerate and amplify the tiniest slights.) Akinnuoye, 19, who was sentenced to 21 years for murder, called Jordan a “batty boy”. “On your mum’s life, I’m straighter than you,” responded Wright, who was autistic. Two hours later, Akinnouye came for him with a small knife and stabbed him in the chest, arms and neck.

One of the challenges of sustained reporting on knife crime is that it takes months for cases to come to trial – and it is only then that the accuracy of the original reports of a killing can be measured against a full account of what happened. In the 39 deaths we chronicled, there have been 24 convictions. In five cases, people have been charged and are awaiting trial. One case has gone to a retrial, and in another six, nobody has been charged, or the person charged has since been released.

In just three deaths – those of 19-year-old Abdullahi Tarabi in Northholt, 15-year-old Koy Bentley in Watford, and 17-year-old Abdirahman Mohamed in Peckham – the accused were found not guilty. After the acquittal of the two 17-year-olds accused of killing Abdullahi, the judge, Nicholas Cooke QC, lamented that “very few people are prepared to help the police … had somebody helped, the outcome might have been different”. Earlier this month, a judge banned five drill artists from referring to Tarabi’s death in songs or on social media.

Of the 41 people found guilty in fatal stabbings (there was often more than one assailant), in cases in which we know the race of the assailant (roughly a third of those convicted were under 18 and so could not be identified), only five were a different race from the victim. When crime is this segregated, it renders the term “black-on-black crime” a nonsense. Unless we are also going to refer to “white-on-white crime” – which we don’t – it makes more sense just to call it what it is: crime. The assailants were often older, with an average age of 19. The oldest person convicted was 48-year-old Leslie Baines, who, along with David Woods, was found guilty of murdering 19-year-old Matthew Cassidy, with whom they had been in a dispute over a drug deal in Connah’s Quay in north Wales.

The youngest were two 14-year-olds, who cannot be named for legal reasons. They were both sentenced to life for killing 18-year-old Saif Abdul Majid in Neasden in north-west London – the result of a dispute that had festered for all of a day. Majid had fought with the two boys the day before, and sustained a facial injury. He saw them in the same place the next day and they set upon him again, stabbing him several times, including a fatal thrust to the neck, before leaving him to die on the pavement.

The average sentence was 19 years. The potentially shortest sentence was for the 15-year-old killer of seven-year-old Katie Rough, who was found guilty of manslaughter due to diminished responsibility and sentenced to a minimum of five years. The girl, who cannot not be named for legal reasons, slashed Katie on her neck and chest in a park near Katie’s home, and then called emergency services to tell them what she had done. The girl had been struggling with mental illness for some time. Her barrister told the court she had been telling people of “delusional and bizarre thoughts” for many months before the killing, including the “genuine belief … that her family and many others were not human and may be controlled by a higher and hostile force”.

The longest sentence was handed down to Aaron Barley, 24, a child of incest who was orphaned at the age of six. He had been given help and support by Tracey Wilkinson in Stourbridge in the West Midlands after she saw him sleeping rough near a supermarket. The Wilkinsons found him work, fed him often and paid for his mobile phone. Not long after they stopped his phone payments, Barley stabbed Wilkinson and her 13-year-old son, Pierce, to death and tried to kill Peter, her husband. He was initially sentenced to 30 years, but a court of appeal decided it was “unduly lenient … in this most exceptional and grave case” and added another five years.

In almost all of these cases, there was clearly a series of social challenges beyond the crime itself: mental health, school exclusions, poverty or unemployment that make the susceptibility to violence – either as a victim or a perpetrator – more likely. By the time the criminal justice system intervenes, it is really adjudicating a crisis that has been created elsewhere.

On the 10th floor of the University of Illinois’s School of Public Health, Dr Gary Slutkin pointed to a map of Chicago bearing round stickers showing where murders have taken place. The north of the city was mostly clear, but you could barely see some of the South Side for all the dots. “It’s the same pattern on a map of the incidence of cholera in Bangladesh,” he said. “This is an infective process.”

I was interviewing Dr Slutkin in January 2013, shortly after a spate of shootings in Barack Obama’s hometown had piqued the curiosity of my editors back in the UK. Slutkin, the executive director of Cure Violence, specialises in infectious-disease control and fighting epidemics, and used to work for the World Health Organisation. He thinks violence behaves like infectious diseases, which can be stamped out by challenging and changing behavioural norms. He showed me a graph of Chicago shootings over several years – a rollercoaster of peaks and troughs. “It’s the same curve for almost every city,” he explains. “It’s an epidemic curve.”

The most significant step in understanding knife crime – and thus in solving it – is to grasp that it is a public health matter. Those who understand it as a criminal issue will seek solutions in longer sentences, stiffer laws, stop-and-search and greater powers for police. That has long been the central response of the state, in London and beyond, and it chimes with the demands of the bereaved and the tabloid and local press.

But it is difficult to find criminologists who agree with that approach. Most insist that tackling poverty and social exclusion would have a far greater impact than tougher policing or sentencing. A public health approach does not deny that policing has a role, but it regards law enforcement as just one part of a broader, more holistic programme of intervention.

“The public health approach,” said Emer Sutherland at King’s College Hospital, “means trying to make it not just about what happened with the stabbing on that day, but looking at the life story of the person in front of you, and the whole of the community in which that one day happened. It means looking at all the ways you can modify things in that life story, and that community, to make that day less likely to come.”

If that sounds like the kind of indulgent liberal tosh that just undermines the law, bear in mind that it is the strategy favoured by the head of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick. “We are all committed to the notion that prevention is better than enforcement, which is, after all, the public health approach,” she said in January.

Dick said most offenders “are people who have suffered some kind of adverse experience of a significant sort when they are young, and/or have limited or problematic family lives and parenting – all things that can lead to other negative outcomes, not just serious violence.”

A few months later, Dick visited Scotland, the one part of Britain that has embraced the public health model. In Glasgow, where the knife-crime problem had been most acute, the police identified the core group of people who were most likely to offend, and a newly created Violence Reduction Unit – which has an arms-length relationship with the police – invited the likeliest offenders to a meeting to discuss the problem. Once there, they were told that if they continued offending, the police would come down on them hard – but were also offered help with housing, employment, relocation and training, and given a number to call if they wanted further assistance.

Of the 39 fatal stabbings of children and teenagers last year, none were in Scotland. This is no panacea: Glasgow still has a murder rate about twice as high as London. But the trend is moving dramatically in the right direction.

Roughly a decade ago, the UN ranked Scotland as the most violent country in the developed world. Between April 2006 and April 2011, 40 children and teenagers were killed in knife deaths in Scotland; between 2011 and 2016, that figure fell to just eight. Glasgow witnessed the steepest decline – from 15 young people in the five years before 2011, to zero in the five years afterwards. Policing did play a role. There was a lot of stop-and-search in the early days of the shift towards a public health approach, and the average sentence for carrying a knife trebled in 10 years. But there was always an understanding that this would never be enough. “You can arrest as many people as you like,” explains Christine Goodall, a surgeon who, along with two colleagues, founded Medics Against Violence in 2008, a campaign group that works with health professionals, law enforcement, social services and other bodies to thwart violent behaviour. “You can search as many people as you like. You can throw away the key if you want to. It just won’t solve the problem.”

Scotland is its own place, and not all of this is replicable elsewhere. But it is a demonstration of what can be achieved if the political will is there. One of the big differences between Scotland and London is political: in Scotland, the public-health approach is funded by and answerable to a single democratic authority at Holyrood.

In London, there are 32 boroughs, and most of the innovative work on youth violence and young people is being done by multiple different charities; the capital does not have the joined-up thinking it needs. Another dramatic difference is that the Scottish police do not have a history of mistrust from the very section of society that a public-health approach needs to engage with. “In London, institutional racism creates a barrier,” argues Susan McVie, professor of quantitative criminology at the University of Edinburgh. “If people see something going wrong, they are less likely to tell the police, because they don’t trust them.”

There is a concerted effort for the rest of the country to learn from Scotland. Last year, the MP Sarah Jones set up the all-party parliamentary group on knife crime, fulfilling a promise she made while campaigning in Croydon, where the issue kept coming up. Jones believes Britain needs a long-term strategy on a par with the last Labour government’s efforts to tackle teenage pregnancy, the rate of which halved in 20 years and continues to fall quickly, even though it is one of the highest in Europe.

The teen pregnancy strategy “was coordinated from the centre,” Jones explained. “It was multi-agency. It was partly about education and making sure they had access to information, it was partly about their life choices, it was partly about funding. It was a broad strategy and I think that’s what we need for knife crime now,” she said.

“The thing that’s both positive and depressing is that a lot of these things we know the answers to. We can fix this. We can stop children dying if we actually have the will.”

Not only do the politicians not have the will – they have not had the facts. For all the ink spilt and speeches delivered about young people and knife crime, nobody could say for sure what they were talking about, because national data on the number of children and teens killed by knives had never been publicly available. Indeed, it is not hard to discern a relationship between the lack of will and the lack of facts – most political responses, from longer sentences to tougher new laws, are prompted by newspaper headlines rather than empirical data.

While it has been impressive to see the work of so many charities, civic organisations and some parliamentarians on this issue over the year, it has also been worrying to see how little strategic thinking the government has done. In April, with stabbings in London all over the news, the then home secretary, Amber Rudd, vowed to do “whatever it takes” to make Britain’s streets safe. Her successor, Sajid Javid, has more recently said he will make tackling knife crime a priority. There is little evidence he has any idea what this would mean. Indeed, it often seemed the government didn’t know any more than our team did – and in fact, since the Guardian obtained the knife crime figures, they knew less.

After almost a year of making Freedom of Information requests, being shunted between the Home Office, the Office for National Statistics and 45 regional police forces, we managed to obtain figures for the last 40 years. The numbers had always been kept – but for reasons that remain unclear, they were not publicly available until we obtained them.

They revealed a complex picture that belied most of the prevalent notions of who is at risk. From 2005-2015, on average, one in five people stabbed to death were female, and one in 10 were under 14. These, too, are victims of knife crime, though they are rarely included in discussions of the issue.

With 39 young people stabbed to death in 2017, we now know that it was the worst year for almost a decade, and the third-worst since 1977, which is why it’s worrying that this year could be worse still. The trend is more alarming than the raw numbers.

When we talk about “knife crime”, one of the major obstacles to understanding the problem has been the disparity between London and the rest of the country. The capital comprises roughly one in eight of the UK population, but is home to around half of young people killed by knives. In the rest of the country, victims are of varying races; in London, they are overwhelmingly black.

But not all of London is equally dangerous. Very few stabbings take place in central London, with most occurring in the outer ring – travel zones three and beyond – as if London seemed intent on replicating the Paris banlieues. Two of the deaths last year, which took place seven months apart, happened in the same London street. The pain is concentrated in certain areas.

And while class is an important factor everywhere, race is undeniably a key factor in London. There is a large population of working-class white and Asian youth in London, and they are not dying in stabbings at anything like the rate of their black peers. In London, there is something particularly deadly about being a young black man.

Still, if we are talking about “knife crime in Britain”, it cannot be reduced to race and culture in the capital – but very often has been. Half of the children killed by knives in Britain are not in London; of those, only around 15% have been black in the last decade. Indeed, taken as a whole, two-thirds of the young people killed by knives in Britain, including London, are not black.

Our obsessive focus on one group of people in one place has hindered our capacity to engage with the far broader range of people in the far broader range of places that are actually being affected. Meanwhile, the punitive responses proposed offer little hope of making things better, and the funding necessary for a public-health approach has not been forthcoming.

It is difficult to adopt a public health approach when your stated agenda is to shrink the public sector. For all the talk of personal responsibility, when it comes to knife crime, there is a general understanding that societies have a collective responsibility for children and young people. But without adequate funding, our capacity to meet those responsibilities is severely diminished.

One Friday evening in the Black Country, I drove around with Bryan Kellsey, looking for a youth club that was open. The first place we went to, in Wolverhampton, had closed down. The next had been vandalised. “Would have been a time, not that long ago, we’d have passed three or four by now,” said Kellsey, who has been a youth worker in this area for decades, as we turn into Dudley’s Wren’s Nest estate, where the community centre was shut suddenly in October, and finally up a dark lane to a facility just off Meadow Road.

In front is a basketball court strewn with litter and leaves; out the back, an adventure playground had long since closed. Inside, the small hall hosts table tennis, pool, table football and an electronic game called Dance Dance Revolution. As dusk gave way to darkness, the smaller children at the kids’ club run by Dudley Community Church left with their parents, and youth workers got ready for the teenagers who were due to arrive for a council-funded session.

Two years ago, Dudley lost around 30 youth workers through voluntary redundancy and redeployment; this year there will be more cuts, with staff being asked to reapply for fewer posts. I asked one of the youth workers where the kids will go instead. “They’ll drink in the parks, hang around and just get in trouble,” she said.

Youth services have not disappeared from Wolverhampton altogether. As the council shut down smaller clubs around the city, some on working-class estates on the outskirts, it went into partnership with local businesses and foundations to set up the Way Youth Zone. The council also gave small grants to voluntary organisations to work with harder-to-reach groups. The Youth Zone stands in the centre of Wolves – a huge, impressive structure offering everything from boxing to indoor rock climbing, a junior gym, music, film, arts, fashion, mentoring and training. Phil Marsh, openings manager for OnSide Youth Zones, described it as a “world-class, 21st-century youth club” – one of a chain of similar centres across the UK.

Everybody agrees it is an excellent facility. But not everyone believes it fulfils the needs of the area. Danny Millard, a youth worker and Labour councillor in nearby Sandwell, said that, by concentrating youth provision in the centre of Wolverhampton, the council is failing to get to those estates most affected by poverty, where young people are most vulnerable to antisocial and violent behaviour. “A lot of the kids you really need to be talking to aren’t going to get on a bus and go into town. You have to go to them and reach them where they are,” he said.

Of the 20 authorities that have faced the steepest cuts in youth work in the last few years, two have been in the West Midlands. Between 2014 -2017, Walsall saw a 67% cut in funding for youth services. In Wolverhampton, it was 86%. Here, the council shut 15 youth centres and 31 “delivery points”, and went from a 100 full-time and part-time workers to just eight full-timers. “They gutted it, basically,” said Millard.

This steep fall in funding has coincided with a precipitous rise in knife crime. In the West Midlands, it has almost doubled in the last five years. More than 1,600 people were cautioned or sentenced for carrying knives and offensive weapons in the West Midlands and Staffordshire last year – the highest rate for eight years. Most of them were young men between 15 and 19 who claimed they were carrying weapons for protection.

One of the two young people killed in West Midlands last year died in Walsall. Already this year, several young people have been stabbed to death in the area, including an eight-year-old girl in Brownhills, near Walsall, and an 11-year-old girl and 15-year-old boy in Wolverhampton.

In April, after a spate of knife and gun deaths, the home secretary insisted that drawing a link between austerity and the increase in crime was “too simplistic”. “I want to hear solutions instead of constant shouts of: ‘Cuts, cuts, cuts!’” she said. But it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, while there are many reasons for knife crime that have nothing to do with funding, some of the solutions reside in reversing those cuts.

Since 2010, resources have been channelled away from young people in all sorts of ways. In 2011, the government scrapped the £30-a-week education maintenance allowance for low-income students in school or college. Between 2010-2014, funding for education for 16- to 19-year-olds fell by 14% in real terms, and more recently there have been severe cuts to urban schools. NHS cuts have also made child and adolescent mental health services far more difficult to access. Children and teenagers have less support financially, socially and emotionally, giving them fewer places to go, fewer things to do and less professional adult supervision outside of school and home. And having created the conditions for more turmoil, the government has then slashed the capacity to deal with the fallout by making swingeing cuts to policing, too.

All of this takes a toll. Quamari Serunkuma-Barnes was stabbed in January outside his school in Willesden, north-west London – the same school that Saif Abdul Majid, who was killed nine months later, had been to. After interviewing Quamari’s parents, I spoke to the mother of the boy who killed him, who tearfully detailed her efforts to steer her son away from violent crime.

On 23 March 2015, she sent an email to her MP with the heading “PLEASE HELP ME SAVE MY SON!!!” She described how the behaviour of her then 13-year-old was “[deteriorating] rapidly, involving himself with the wrong crowd”, and her fears for the impact this could have on his siblings. She detailed how she had enrolled herself in parenting classes, consulted with social workers and psychologists, sought referrals for mental health assessments, requested to move him from his school and asked for help to move her family out of London, but felt she was getting nowhere.

At the bottom of many of the responses from Brent council came the impersonal sign off: “Brent Council needs to save £54m over the next two years. Find out more about our budget consultation events and have your say before February 4th, 2015.”

At King’s College Hospital in London, the busiest day for young knife victims is Saturday; but on an average day, as many kids come in wounded between 4pm and 6pm as between 8pm and 10pm. “You get a big peak after school,” explained Emer Sutherland. “And then a big peak about 9.30pm before they go home. For the older kids, it could be any time day or night. We get kids getting stabbed on the way to school.”

Sutherland reviews the notes of every young person admitted each week. “I know some of these names,” she said. “I know their stories. So I know that quite often we’ve seen them before and we’re getting them back.”

Without the numbers, we can’t possibly know the scale of the problem. But it’s only through the stories behind those numbers that we can begin to navigate how those numbers might be reduced.

Vernon, 19, came in to King’s around 8pm. He had been waiting for friend on a south London estate when he sensed a man looking at him across the road. He started cycling away when the man chased him in a car, knocked him down and then started hacking at him with a machete. He sliced away at Vernon’s body, almost severing a finger before leaving him lying in the road with his face slashed. A woman heard the screaming and brought towels for the blood and called an ambulance.

“I was just thinking, I’m about to die,” said Vernon when I spoke to him in January. “I was asking in the ambulance, ‘Am I going to die, am I going to die?’ And they kept saying: ‘No, you’re not going to die.’”

The next morning, Alex, a senior youth worker from Redthread, scanned the referrals from the night before, read the hospital notes and then went up to find Vernon with casts on his hands and legs, and a huge bandage on his face.

They bonded over football, with Alex ribbing Vernon over his support for Arsenal and Vernon giving as good as he got. Alex, who had seen several cuts like this in the past, mentioned bio oil, which can help with scar tissue, and offered to get some for Vernon if he came and saw him when he was discharged.

Vernon was in for a few days – plenty of time to reflect on what he had been through and why. “I was just looking at the air and crying really, thinking, ‘Why did I go out today?’” he said. “My face is never going to be the same again. My life is pretty much done now.” He had been about to go back to university in Northampton, where he had just finished his first year of business studies.

“I always thought a stabbing could happen to me,” he said. “Not because of anything I did. But because some of the people I associated with used to hang around with the kind of people that might happen to. But I never thought it would actually happen, because I didn’t know them or hang around with them. I would just hear stories about the kind of stuff they would do.”

The second day, Alex opened up a sensitive line of questioning. “We didn’t chat about it yesterday, but that’s a lot of shit that you’ve been through,” he said to Vernon. “If it was me, I’d be thinking: Who’s done this? Why have they done this? They’re not going to get away with this. Justice needs to happen.”

Vernon nodded. “I’m pissed off. I want to find out who did it. This shouldn’t have happened to me. I’m going to find out who did it.”

This, said Alex, was the teachable moment. Vernon was in a place to think about safety and retaliation in a safe setting. “There’s imprints on your body and imprints on your mind,” Alex explained. “It’s actually easier for your body to recover … but your mind can quickly go back to remembering what happened. And can quickly go back to the anger and emotions as well.”

Alex told him that thoughts of retaliation and revenge are normal, but asked if Vernon thought he’d feel good about himself if he went through with it.

“But where’s the justice?” asked Vernon. “What happens from here? This youth is going to get away with it and I’m left with this scar.”

“I can’t answer some of these questions,” said Alex. “You feel that rage, and that’s normal. But you’re in a position now to decide what happens. So you could be thinking, ‘Since my time in hospital I’ve started running three times a week and got my life together.’”

Alex had planted a seed. It took a while to reach full bloom. “When I came out of hospital, my friends were egging me on for vengeance,” says Vernon. “They were saying: ‘We need to do something about this’. And I thought we needed to as well. Over time, I just sat down and realised, why would I risk my freedom and my life for something that didn’t actually kill me and is healing anyway?

“It was a difficult conclusion to come to, pride-wise. It hurt. But I talked myself out of it. Because it’s not worth it. My friends didn’t really say much. But I could see there was a disappointment. I’d let the person get away with it.”

Alex kept visiting, bringing questionnaires that Vernon liked to do, gauging his emotional wellbeing. Meanwhile, Vernon resolved to make some changes. He decided to drop the course he was doing at university, which he wasn’t enjoying, and study closer to home. Alex scoured job ads, sending him notices of vacancies for football-coaching courses and a civil-service apprenticeship, based on the kinds of things Vernon had said interested him. He also got a temporary job and started mixing up his friendship circle.

“I feel like I’ve got my own mind now. I’ve made decisions to better my life. It has elevated me to a different level. We’re not at the same level that we used to be. They were dragging me down a bad route.”

Additional reporting by Caelainn Barr and Damien Gayle.

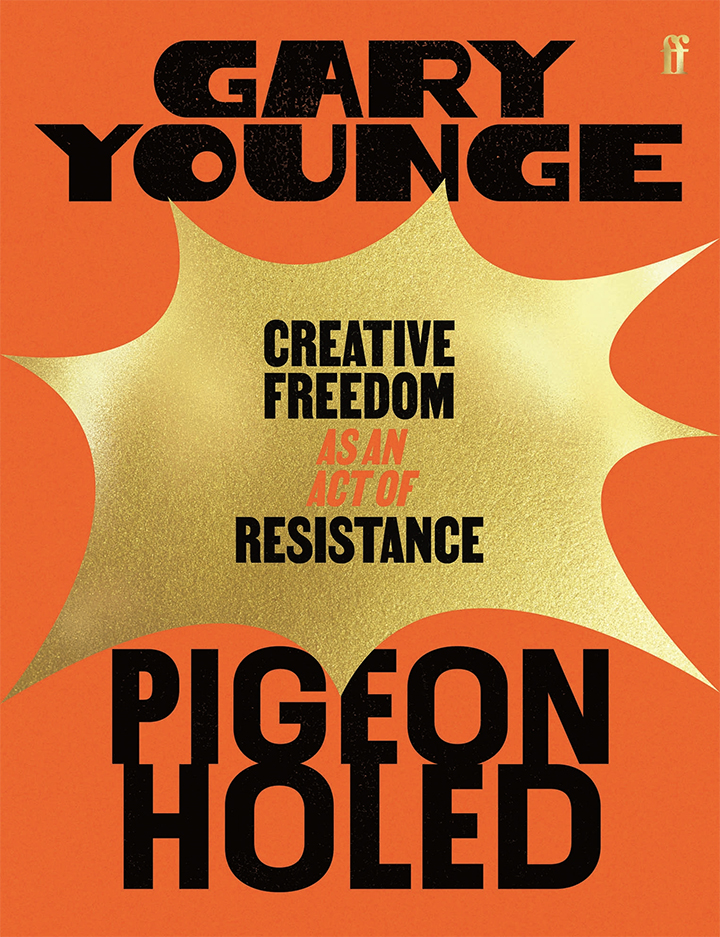

Main image: (clockwise from top left) Katie Rough, Abdullahi Tarabi and Koy Bentley

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.