Last month, two German-born Premier League footballers of Turkish descent, Mesut Özil and Ilkay Gündoğan, posed for photos with the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, while he was in London. Gündoğan, who has both a German and a Turkish passport, signed his shirt: “To my president, with my respects.”

During recent national friendlies, Özil and Gündoğan were booed by German fans – and reprimanded, but ultimately backed, by the German Football Association. They have been told they can expect more animosity from fans as the tournament progresses.

There are good reasons why you might boo a football star who meets Erdoğan. Given his record of human rights abuses and dictatorial tendencies, it’s the kind of photo-opportunity you should turn down. As Sevim Dağdelen, a leftwing German MP of Turkish descent, pointed out: “It’s a crude foul to pose with the despot Erdoğan in a luxury hotel in London and dignify him with the title ‘my president’, while in Turkey democrats are persecuted and critical journalists are detained.”

But there are poor reasons to boo them too. Some, in Germany and elsewhere, struggle with the notion of multiple national identities – that people, particularly those with a history of immigration in their family, might feel an allegiance to more than one country. “Integration is supposed to be give and take,” Zelika Baba, a Berlin-based youth worker of Kurdish and Aramaean descent, once told me. “But they just want us to give up our culture. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve lived here – whether you were born here or whether you speak German – you’re always a foreigner. They talk about us, but they never talk with us.”

MPs for the hard right Alternative für Deutschland have seized the moment to question not just the players’ decision, but their authenticity. “Why is Gündoğan playing for the German national team when he recognises Erdoğan as his president?” asked one. The World Cup is upon us, showcasing not just some of the greatest footballing talent but also giving free rein to the rawest and deepest anxieties both within nations and between them. During a period of heightened nationalism in Europe, we are about to enter a month of ostentatious flag-waving and anthem-singing, and momentary, patriotic euphoria, delusion or disappointment – often all of them. “The imagined community of millions,” the historian Eric Hobsbawm once wrote, “seems more real as a team of 11 people.”

The trouble is that the reality – as seen on the football field – often fails to match up to the imagination, tended to over decades of mythology. These tensions need not necessarily have anything to do with race or ethnicity. When Italy failed to qualify for this tournament for the first time in 60 years, some put it down to corruption, comparing themselves unfavourably to Germany “which follows the rules”.

In 2002 Ireland captain Roy Keane was sent home after he told the team manager, Mick McCarthy: “I didn’t rate you as a player, I don’t rate you as a manager, and I don’t rate you as a person. You’re a fucking wanker and you can stick your World Cup up your arse. I’ve got no respect for you.” Those who dismissed this as just one more tantrum of the overpaid and uncouth missed the parallels with the broader ruptures in Ireland at the time, argued commentator Fintan O’Toole. “[Keane] is the perfect exemplar of the new Celtic Tiger Ireland ... Like the new Ireland, he is rich, upwardly mobile and driven by a ruthless work ethic ... Around it there is the lingering legacy of a relatively poor society in which it made sense to be grateful for small mercies.”

But given the nature of Europe’s anxieties and the fact that, outside of the criminal justice system and unemployment lines, football teams are one of the few places where minorities are likely to be overrepresented, issues of racial, ethnic and national identity often feature heavily. Zlatan Ibrahimovic believes the reason he has been left out of the Swedish team has little to do with his injury. “I do not have a typical Swedish name and I do not have the typical Swedish attitude and behaviour.” The most diverse English squad to date, wary of the notoriety of racism in the Russian stands, posed with Show Racism the Red Card signs.

Interpretations of what these moments might mean can be overdone. When France won the World Cup in Paris in 1998 with a very multiracial and multi-ethnic team, the nation came out to celebrate. “What better example of our unity and our diversity than this magnificent team,” said the Socialist prime minister, Lionel Jospin.

Apparently we don’t always learn from our examples. Four years later Jean-Marie Le Pen, the then leader of Front National, entered the presidential election runoff after beating Jospin into third place. Eight years after that, in South Africa, the entire French team went on strike after a black player was sent home for insubordination. The philosopher Alain Finkielkraut echoed many a racist when he compared that team to youths rioting in the working-class suburbs. “We now have proof that the French team is not a team at all, but a gang of hooligans that knows only the morals of the mafia,” he said.

England has an inflated sense of its own capacity based on our former glory – a fact we struggle to come to terms with

Herein lies a central tenet of western racism. When diversity is related to something successful then it is a sign of the nation’s genius in allowing, nurturing and managing it; when it is attached to a national calamity, diversity is the reason for the failure. Some, in Italy, have predictably blamed their poor showing this year on “foreigners”. “Too many foreigners on the field,” Matteo Salvini, the leader of the anti-immigrant League, tweeted. “#StopInvasion, and more space for Italian guys, also on the soccer field.”

But in few places is Hobsbawm’s “imagined community” more apparent than England, where “the team of 11 people” doesn’t stand as a proxy for national identity – it is virtually its sole exemplar. Unlike Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, who have assemblies or parliaments, England rarely exists in a material form apart from as a football and rugby team. (The cricket team can include players from throughout the UK and Ireland.)

This is particularly unfortunate because it concentrates the “nation’s” identity in a sport which, thanks to former glory, promises unrealistic nostalgic pretensions of greatness that are unlikely to be repeated. Sound familiar? The problem is not that we underperform but that we have actually found our level. “England do just fine,” wrote Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski in their book Why England Lose. “They perform even better than expected, given what they have to start with.”

So England has an inflated sense of its own capacity based on a gilded past – a fact it constantly struggles to come to terms with. Whether it crashes out in the first round or goes all the way, rest assured, however England fares will be seized on – by half the country – as a metaphor for Brexit.

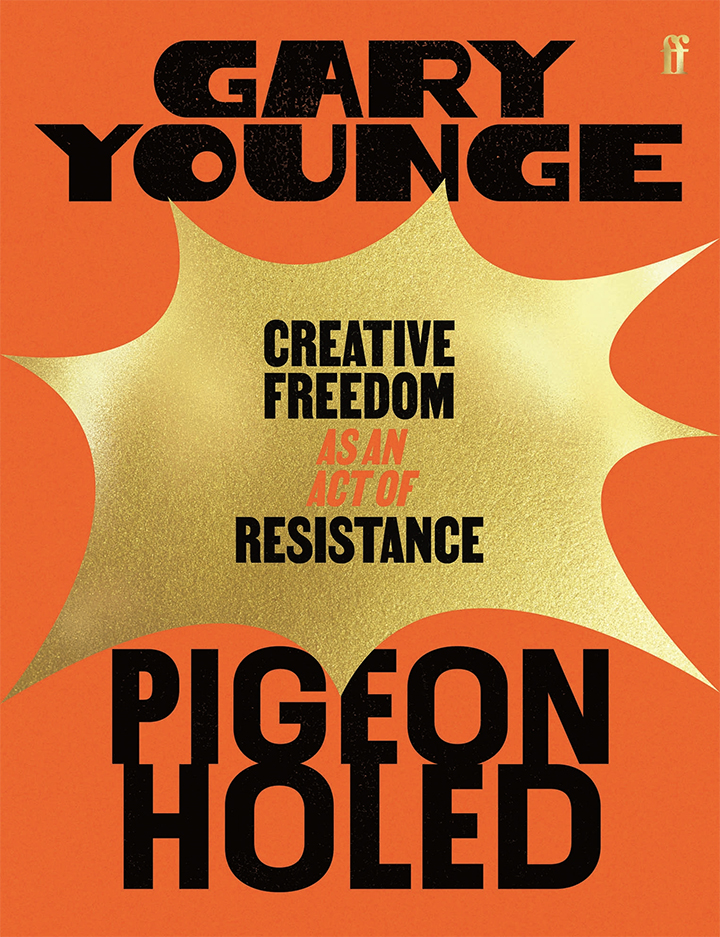

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist